By Russell Nichols

For the past four years, Sen. Scott Wiener (D-San Francisco) has been pushing to decriminalize psychedelic drugs — but every time he writes a bill on the matter, policymakers in California just say no.

The latest was Senate Bill 1012. It would’ve given adults the green light to use certain psychedelic substances for therapeutic purposes under strict supervision by a licensed facilitator in a controlled environment. In May 2024, the bill stalled in the Senate Appropriations Committee. A similar bill was vetoed in 2023 by Gov. Gavin Newsom, who suggested the state establish “regulated treatment guidelines.”

Wiener won’t quit.

“We’ve been working for four years to legalize access to psychedelics in California, to bring these substances out of the shadows and into the sunlight, and to improve safety and education around their use,” Wiener said in a statement. “… I’m highly committed to this issue, and we’ll continue to work on expanding access to psychedelics.”

As his psychedelics bill died in committee in 2023, about 60 miles north on Highway 49, another psychedelics project was coming to life in Grass Valley. This one was 30 years in the making, birthed by Brian Chambers, a psychedelic art collector who also seeks to bring psychedelics to the mainstream, but through surreal pieces instead of state policy.

In spring 2024, he launched the Psychedelic Arts and Culture Trust (PACT) to educate the public on the past, present and future impact of psychedelics on visual art and culture. Curious minds can learn about substances like ayahuasca, DMT, LSD, peyote and psilocybin (magic mushrooms), and how they influence the mind and induce hallucinations — a side effect known to inspire art creation and affect the art viewing experience.

PACT is an offshoot of The Chambers Project, an 8,000-square-foot gallery and community center in Grass Valley, established in 2021 by Chambers and co-owner Leah Plenge. The gallery mainly exhibits psychedelic art. After the inaugural PACT symposium in August 2024, the gallery has hosted several events, such as a Q&A with Bill Walker, the legendary Grateful Dead album cover artist. Other events have included comedy shows, music events and glassblowing workshops. The next show will take place March 8, 2025, with a focus on optical art.

“With the resurgence and destigmatization and social and medical acceptance of all things psychedelic, it feels like a prime time to really stamp ourselves as the epicenter of the psychedelic art movement,” says Chambers, who has a personal collection of more than 300 trippy works.

Emerging from the “Summer of Love” scene in 1960s San Francisco, psychedelic art used “brilliant colors and mind-bending images to represent the freedom of ideals and expression of the era,” according to Lynn Sanborn, archivist librarian at the Sacramento State Library.

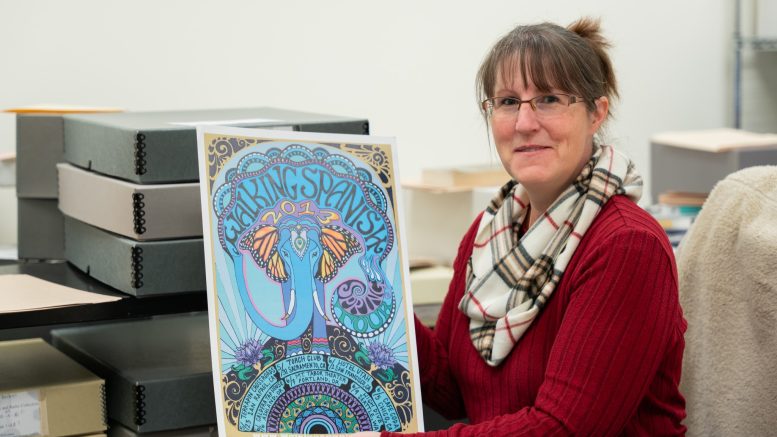

From concert posters to handbills, this vibrant artwork celebrating music, activism and Sacramento history can be found in the Sacramento Rock and Radio collection at Sacramento State’s Gerth Special Collections & University Archives.

“This art style continues to have significance today,” Sanborn says, “and has evolved to showcase the flowing styles representative of a new age.”

Growing up in the 1980s in Tennessee, Chambers was captivated by surrealists like Salvador Dalí. He became immersed in psychedelic art in the mid-1990s. That was when he read the classic road trip opus “Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas” by Hunter S. Thompson. In high school, his science teacher showed the class an Alex Grey poster, which Chambers learned was inspired by LSD.

After discovering Rick Griffin and the other San Francisco artists from the ’60s concert poster movement, Chambers was hooked. In 2008, he connected with artist Mario Martinez — who goes professionally by Mars-1 — which would shape his path in commissioning live, collaborative artwork.

“I enjoy pairing different artists together so that they can teach and learn from each other,” Chambers says. “And I’ve definitely found that the sum of a couple artists is greater than anything that they can do on an individual level.”

For years, Chambers had been doing his highest profile showcases in San Francisco, Denver, Miami and New York. But four years ago, when COVID hit, he realized the gallery landscape was changing. His kids were also getting older. He wanted them to be able to see his work as a collector locally and says he felt like he was cheating his local community by working elsewhere.

“That’s when I really decided to level up and buy the building that we’ve currently got,” says Chambers, who does psychedelics. “So it’s a big blank canvas with plenty of room to grow and do some amazing things. And with this community that’s so embracing of everything that we’re doing, it seems to be working.”

Various scientific studies highlight the potential benefits of psychedelics. Supporters include veterans who have used psychedelics to treat PTSD, and parents who used psychedelic therapy to help their children overcome addiction.

But the stigma is hard to shake — especially when opponents highlight insufficient evidence.

Critics to Wiener’s bill include some medical professionals, such as the California State Association of Psychiatrists, which expressed that “evidence to support the therapeutic use of psychedelics is not yet robust enough to justify widespread access, especially for unsupervised use or use in the presence of non-medical individuals.”

This fine line is familiar to Justin Lovato, a surreal, psychedelic artist who believes these substances shouldn’t be taken lightly.

Growing up in South Sacramento, with his father being a painter, Lovato was drawn to alternative art spaces and underground shows. One of his biggest influences was The Toyroom Gallery, a lowbrow, pop-surrealist street art gallery. This was where he sold his first paintings in 2005, making about $800.

“It made me think maybe it was possible to live off of it,” he says, “and that turned out to be true. A part of it was me committing to being an artist and not going to school for anything else. Not giving myself a choice. No backup plan.”

After he relocated to the Bay Area in 2010, Lovato took a trip to Grass Valley where he met Chambers and was introduced to the wild world of psychedelic art. Under the influence of psychedelics, Lovato’s art grew even more surreal than it was when he started.

“Psychedelics do have the effect of making synapses connect where they don’t usually,” Lovato says. “… It also has the effect of making your mind flow freely. Ideas will pop up. If you’re lucky, you can take a note and grab one — one in 10 is actually a good idea.”

But Lovato believes the conversation is a nuanced one. For instance, he says psychedelics are not a panacea or “the only path to fulfilling yourself spiritually or creatively.” And certain mental illnesses can become intensified without proper supervision, he adds.

“Psychedelics are kind of playing with fire,” he says. “It can be productive and sometimes it can be potentially treacherous. I think psychedelics are a tool to create feedback loops in your mind, so your previous experiences affect your [psychedelic] experiences.”

That said, he can’t deny the positive influence psychedelics have had on him. Lovato says Chambers has been the most important person in his art career by providing unique opportunities in a niche area of the art world where he feels he fits in.

“What he’s doing is important and historical,” Lovato says, emphasizing his mission to bridge psychedelic art history with the modern era. “… And I think he is the aggregate for the psychedelic art that’s coming out into the world.”

This story was funded by the City of Sacramento’s Arts and Creative Economy Journalism Grant to Solving Sacramento. Following our journalism code of ethics and protocols, the city had no editorial influence over this story and no city official reviewed this story before it was published. Our partners include California Groundbreakers, Capital Public Radio, Outword, Russian America Media, Sacramento Business Journal, Sacramento News & Review, Sacramento Observer and Univision 19

Well The State would ruin this like weed and La in no time

I love drugs but it is bad journalism to mix personal enjoyment of psychedelics with the possible medicinal uses. This article blurs the lines between fun drugs and drugs for medical purposes. The author does not draw a clear line between the medical uses and the “fun” uses. I do not disagree with decriminalization, but that won’t happen if we pretend that recreational drugs and medical drugs are the same thing.