By Robert Victor

Winter begins with the solstice on Dec. 20-21, at 1:21 a.m., during our longest night. There are plenty of dark skies in December, and lots of planets to be seen, especially in evening hours!

On Dec. 1, nearly 1 1/2 hours after sunset, around the end of twilight, brilliant Venus (magnitude -4.2) is low in the southwest; Saturn (magnitude +1.0) reaches its high point in the south; and Jupiter (magnitude -2.8) is low in the east-northeast. About 1 1/2 hours later, Venus sets while Orion and Gemini rise into view. Another 1 1/2 hours later, or 4 1/2 hours after sunset, look for Mars (magnitude -0.5) low in the east-northeast, Procyon low in the east, and Sirius (magnitude -1.5) low in the east-southeast. Note four brightest “stars” are now Venus, Jupiter, Sirius and Mars, but not all are visible simultaneously until about mid-December, when Sirius, rising four minutes earlier daily, rises before Venus sets.

On Dec. 11, Mars rises just before Venus sets. On what date will you first see the lineup of four planets—Venus-Saturn-Jupiter-Mars—simultaneously? By Dec. 20, Venus and Mars will be 5° above opposite horizons three hours after sunset. The lineup of Venus and all five outer planets —Venus-Saturn-Neptune–Uranus-Jupiter-Mars—then spans 169°. If you’re surrounded by mountains, go elsewhere for a vantage point with unobstructed views toward the west-southwest and east-northeast, or wait several days as the lineup shrinks in extent. On Dec. 31, Venus (magnitude -4.4) and Mars (magnitude -1.2) will be 154° apart and 13° above opposite horizons about 2 1/2 hours after sunset.

Jupiter’s brightness changes little this month, as it reaches minimum distance from Earth and maximum brilliance at opposition, with all-night visibility on Dec. 7, when Earth passes between Jupiter and the sun. That same night, Mars begins retrograde just 2° northwest of the Beehive (use binoculars to see that cluster’s individual stars), and Neptune ends retrograde 0.65° east-northeast of the 5.5-magnitude star 20 in Pisces, end of the handle of a dipper-shaped asterism. Jupiter and Uranus retrograde all month, with Jupiter reducing its distance east-northeast of Aldebaran from 8.4° to 5.7° in December, while Uranus shifts only 1° during the month, ending 8° southwest of the Pleiades.

Retrograde, an apparent backward (westward) motion of a planet against the stars, occurs when one planet overtakes another, and the sight line from either planet to the other rotates clockwise when viewed from north of, or “above,” the solar system, even though all the planets revolve counterclockwise. So, when we see Mars retrograde, an observer on Mars will see Earth retrograding. Even inner planets retrograde, as Mercury is doing Nov. 26-Dec. 15. But the middle of an inner planet’s retrograde isn’t well seen, because you’d be looking right into the glare of the sun. When you face an outer planet in the middle of its retrograde, you’re looking directly away from the sun.

Saturn appears at an unusually dim magnitude +1.0 in December, and will continue to fade because its rings are tipped from edgewise by only 5° on Dec. 5; 4° on Jan. 7, 2025; 3° on Jan. 28; 2° on Feb. 16; and 1.5° on Feb. 25, when Saturn will set in twilight. Rings will be presented edge-on toward Earth and the sun on March 23 and May 6, 2025, respectively. So when Saturn emerges into the eastern dawn sky in mid-April 2025, Earth, but not yet the sun, will have crossed to south of the ring plane. The rings will then be essentially invisible, because their unlit side will be tipped slightly into our view.

It’s early spring in Mars’ northern hemisphere. The planet’s north polar region now appears very bright and large, as the North Polar Hood (cloud cover) clears and reveals the North Polar Cap of frozen water and carbon dioxide at the surface. You can also look for Mars’ dark surface feature, Syrtis Major, best seen when near the center of Mars’ tiny disk about 36 minutes later daily. From the Western U.S., look on Dec. 19 at 10:34 p.m.; Dec. 20 at 11:10 p.m.; Dec. 21 at 11:47 p.m.; Dec. 23 at 12:24 a.m.; Dec. 24 at 1 a.m., and so on until Jan. 2 at 6:26 a.m.

In the morning sky, Mercury emerges quickly after perihelion and inferior conjunction of Dec. 5-6. Can you spot it by Dec. 12? It brightens through magnitude +1.3 on Dec. 12, +0.9 on Dec. 13, 0.0 on Dec. 17, and -0.4 Dec. 22-31. Mercury-Mars-Jupiter span 171° Dec. 13-17. Mercury lingers 7° from fainter Antares Dec. 20-26 and reaches greatest elongation, 22° from the sun, on Dec. 25.

Follow the moon: On Dec. 2, in evening twilight half an hour after sunset, look for the 3 percent crescent moon very low in the southwest, 24° to the lower right of Venus. On the next evening, look within an hour after sunset to find the 8% crescent moon just 12° to Venus’ lower right. In a spectacular sight on Dec. 4, the 15% crescent moon with earthshine on its dark side passes within 3° south (to the lower left) of Venus. Through a telescope, Venus’ disk, 18” (arcseconds) across, shows its phase, two-thirds illuminated. Venus is far in the background, in place to catch more sunlight than the moon. On that evening, a magnification of slightly more than 100-power would make Venus appear as large as the moon does with the unaided eye. From now until March, Venus will grow in apparent size, but show less of its illuminated face as Venus draws closer and begins to swing between Earth and the sun. On Dec. 5, the 23% crescent moon will appear 13° to Venus’ upper left.

On Dec. 7 and 8, the moon flips from a 44% crescent to a 55% gibbous, skipping from 10° west to 5° east of Saturn, and past first quarter phase, when the moon would be half full and 90° from the sun.

On the evenings of Dec. 13-15, the waxing gibbous moon coasts eastward through the constellation Taurus, passing the Pleiades cluster, Aldebaran and the Hyades cluster, Jupiter, and Beta and Zeta Tauri, the tips of the Bull’s very long horns. The two star clusters are wonderful sights for binoculars, especially on nights when the moon isn’t nearby or too bright.

Bright moonlight also interferes with the peak of the Geminid meteor shower on the night of Dec. 13-14. The moon is full on the night of Dec. 14, and during that evening, Jupiter appears midway between the moon and Aldebaran, 7° from each.

After it passes full, you can follow the moon by staying up later each night, or more conveniently, by switching your viewing time to mornings, perhaps one to 1 1/2 hours before sunrise. As the moon is about to set on the morning of Dec. 14, you’ll note bright Jupiter, 6° to the moon’s left. On the next morning, December’s northernmost moon will appear 12° above Jupiter. On the morning of Dec. 17, the 94% moon passes 2-3° south of Pollux, the brighter of Gemini’s “twin” stars. (The other is Castor, 4.5° away.) On the morning of Dec. 18, the 88% moon appears just 2° east of Mars. Several hours earlier, during the midnight hour, the moon’s southern edge passes within half a degree—a moon’s width—to the north of Mars. On the morning of Dec. 20, spot the star Regulus, heart of Leo, 3° west of the 72% moon. On Dec. 24, Spica in Virgo is within 3° east (to the lower left) of the 35%, now crescent moon. On Dec. 27, find the 11% crescent moon low in the southeast, with Antares, heart of Scorpius, 12° to its lower left and 8° right of brighter Mercury. On Dec. 28, find Mercury 9° left of the 6% moon. Antares, very close to the moon’s upper left, shows up quite well in binoculars. The last chance to see the moon during this cycle of phases will be an old, 2 percent crescent rising in bright twilight on Dec. 29, about 9° to the lower right of Mercury.

After the new moon of Dec. 30 at 2:27 p.m., your next chance to spot the moon will be about half an hour after sunset on New Year’s Eve, a 2 percent young crescent, within 27 hours past new, and 34° to the lower right of Venus. Binoculars, clear skies and an unobstructed view of the west-southwest horizon are recommended. The 2.1-day-old crescent on the evening of Jan. 1 will be much easier. Happy New Year!

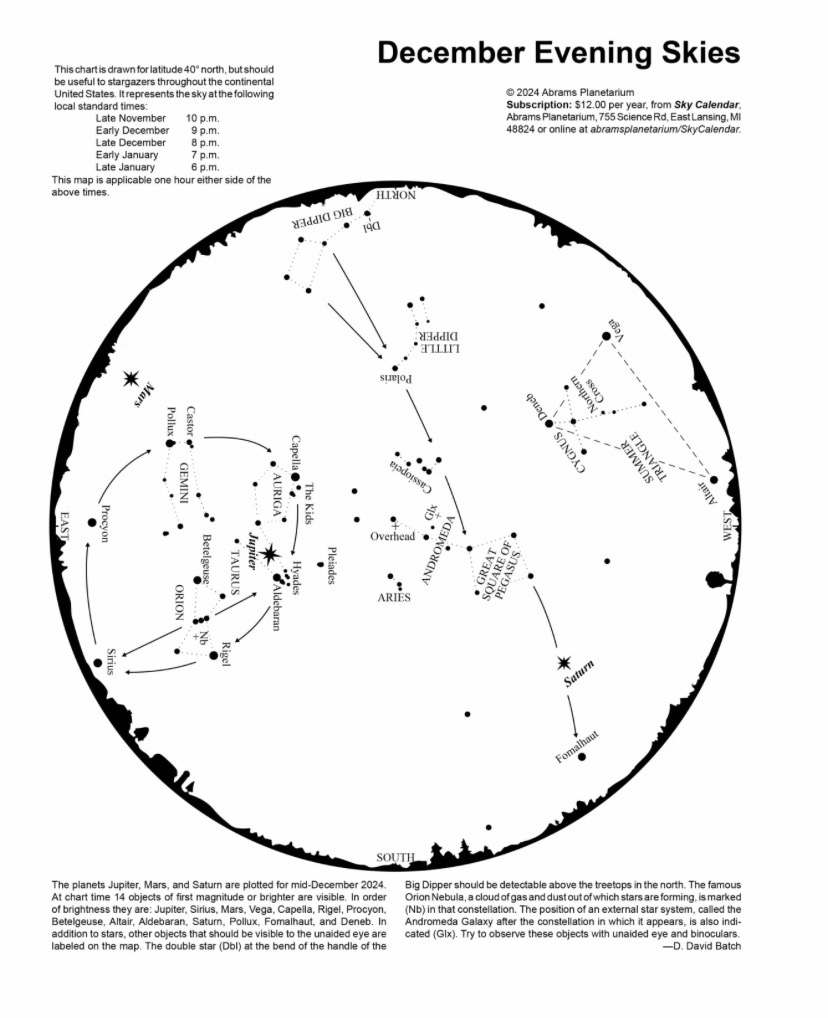

The December Evening Skies map most closely depicts the sky as seen from the vicinity around 9 p.m. on Dec. 4; about four minutes earlier on each successive day until around 8 p.m. on Dec. 19 and 20; and around 7 p.m. on Jan. 4. An unusual feature of the sky then is the presence of 11 stars of first magnitude or brighter above the horizon simultaneously. In December, the three bright outer planets, in order from west to east, Saturn, Jupiter and Mars, increase the total number of objects of first magnitude or brighter to 14, listed in order of brightness in the caption of that map.

Of course, from many locations in the area, mountains will block the view of some of these 14 objects, but within the span of an hour, it should be possible to observe all of them, by looking for Altair earlier than the listed times, and looking for Procyon, Sirius, and Mars later.

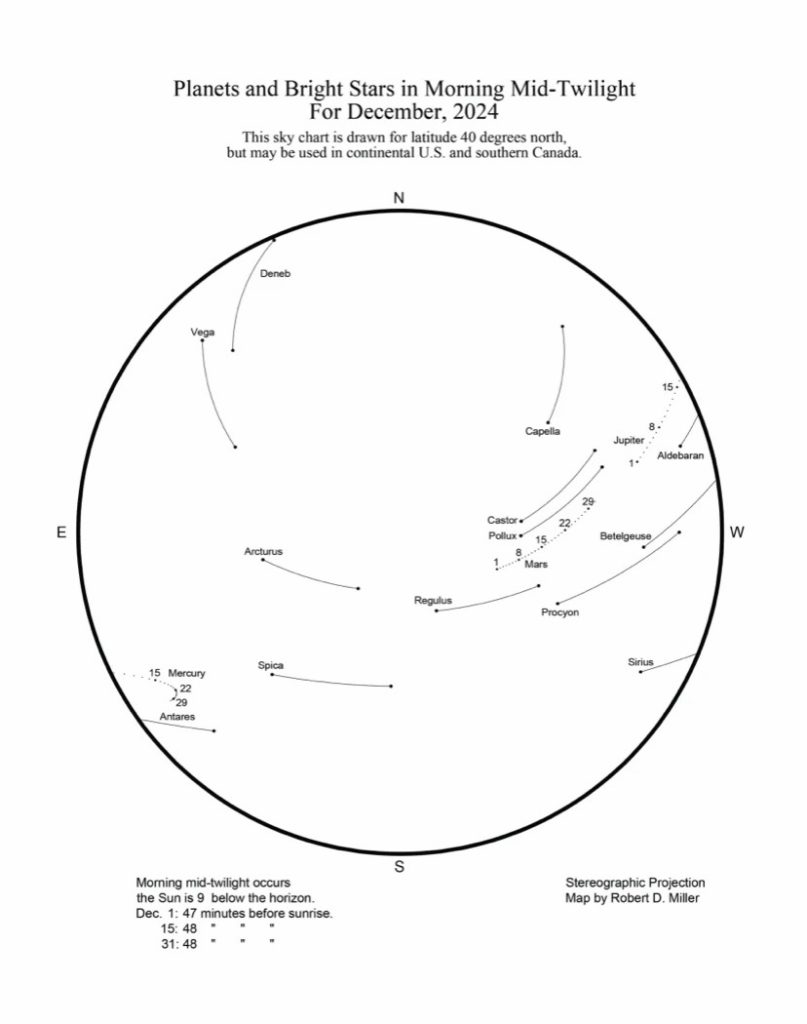

As always with this column, Robert D. Miller kindly provided two charts depicting December’s sky at evening and morning mid-twilight. We defined mid-twilight to occur when the sun is 9 degrees below the horizon. From the Sierra and the surrounding area in December, mid-twilight occurs slightly more than three-quarters of an hour after sunset, and again at the same time difference prior to sunrise.

Planets featured at evening mid-twilight in December are Venus in the southwest, higher as month progresses; Saturn crossing through the southern sky; and Jupiter ascending in east-northeast to east. Bright stars include the Summer Triangle of Vega, Altair and Deneb still well up in western sky, but descending; Fomalhaut, mouth of the Southern Fish, below Saturn; Capella, the Mother Goat star, ascending in northeast; Aldebaran, eye of Taurus, climbing in the east-northeast to east, to the lower right of Capella. Within two weeks before end of year, Orion’s two brightest stars appear: red Betelgeuse, rising north of east, and blue-white Rigel rising south of east, with his belt, a vertical line of three stars, between them. (The belt stars aren’t plotted in the twilight charts, because they’re of second magnitude.)

In December’s morning sky, the brightest “stars”—Jupiter sinking in the west-northwest, and Sirius sinking in the west-southwest—disappear below the horizon at mid-twilight around mid-month. That leaves reddish Mars in the western sky as the champion of the mornings after the departure of Jupiter and Sirius. Ranking next in brilliance for much of December are three stars shining near magnitude 0.0: Arcturus, high in east to southeast; Vega, climbing up from the northeast horizon; and Capella, sinking into the northwest. Mercury, very low in the east-southeast to southeast and brightening through magnitude 0.0 on Dec. 18, ranks next after Mars for the rest of the month, but it might not seem so, because it’s immersed in the glow of twilight. Yet this is a very favorable apparition of Mercury, with the planet 9 degrees above the horizon at mid-twilight for nine mornings, Dec. 18-26. Watch for Mercury-Mars-Jupiter reaching their minimum span, 171°, Dec. 13-17.

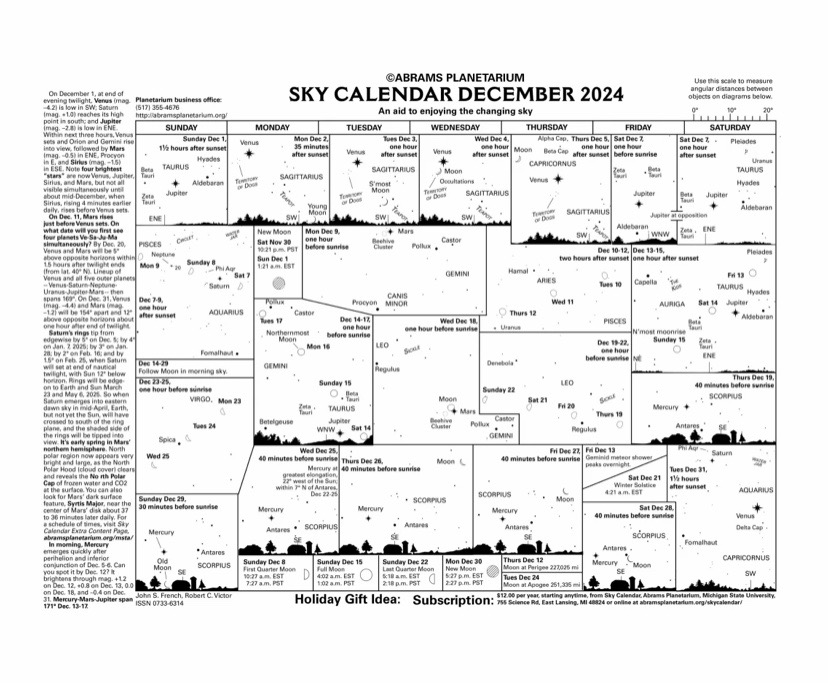

These events, and other gatherings of the moon, planets and stars, are illustrated on the Abrams Planetarium Sky Calendar. A sample December 2024 issue is available by clicking here. The Sky Calendar is also available by subscription from www.abramsplanetarium.org/skycalendar. For $12 per year, subscribers receive quarterly mailings, each containing three monthly issues.

Robert Victor originated the Abrams Planetarium monthly Sky Calendar in October 1968 and still helps produce an occasional issue. He enjoys being outdoors sharing the beauty of the night sky and other wonders of nature. Robert Miller, who provided the evening and morning twilight charts, did graduate work in planetarium science, and later astronomy and computer science at Michigan State University, and remains active in research and public outreach in astronomy.

Be the first to comment on "December skies: The month brings the longest night of the year—and great views of planets"