By Nigel Duara and Joe Garcia for CalMatters

From their phones and their television screens and sometimes out their windows, Californians saw their state change quickly in the pandemic. Homelessness grew then and continued to grow. Fatal fentanyl overdoses soared. Brash daytime smash-and-grab robberies floated from TikTok to nightly newscasts.

A constellation of law enforcement, prosecutors and big-box retailers insisted the cause was simple: Punishment wasn’t harsh enough.

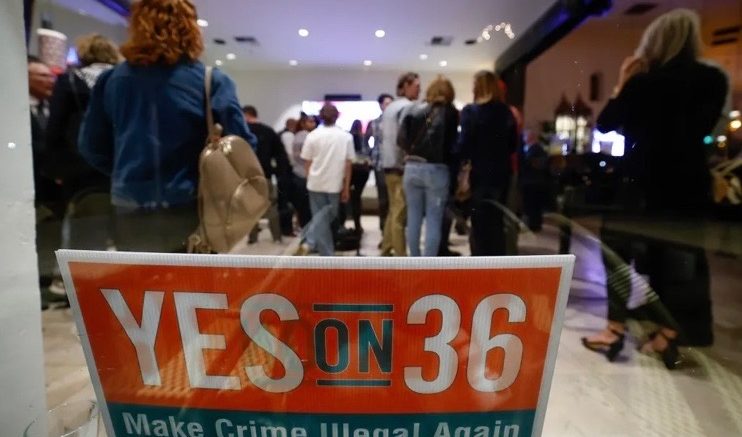

They put forward a measure that elevated some low-level crimes to felonies and created avenues to coerce reluctant people into substance abuse treatment. That measure, Proposition 36, passed overwhelmingly Tuesday night. It led 70% to 30% early Wednesday.

It undoes some of the changes voters made with a 2014 ballot measure that turned certain nonviolent felonies into misdemeanors, effectively shortening prison sentences. Amid the pandemic’s visible changes to California, in its growing homeless encampments, its ransacked Nordstroms and its looted rail yards, critics of that previous initiative finally found the right climate to turn back the law.

The strategy at the center of Prop. 36 is still a matter of debate. Its opponents say harsher sentences will never be an effective deterrent to crime. Much of the science, some of it funded by the U.S. Department of Justice, backs them up.

But the victory of Prop. 36, despite opposition from the governor and most of the state’s Democratic leadership, was not about what people know, it’s about what they saw.

An IT technician was afraid to walk five blocks to work in downtown Los Angeles, so he bought a parking pass and drove. A big-box retailer moved all of its goods to its second floor because people kept stealing from the ground floor. The fentanyl crisis had police on body camera videos panicking and fainting when exposed to the substance.

The Prop. 36 campaign ran on images like those, and it promised to make them go away.

That Prop. 36 would pass has been fairly clear since late summer, when Gov. Gavin Newsom’s last-ditch attempts to preempt the measure with other retail crime bills failed to siphon funding from Prop. 36 or to keep it off the ballot. So how did Californians, who supported more lenient sentences under 2014’s Proposition 47, come to support a tougher crime measure a decade later?

“What we might be seeing is evidence of a course correction of a long path of criminal justice reform efforts,” said Magnus Lofstrom, criminal justice policy director at the Public Policy Institute of California. Prop. 36 “targets crime and social problems that people can see: retail theft, more merchandise locked up, more viral videos (of thefts) and then the media talking about all of it.”

It’s those visible problems, Lofstrom said, that can quickly change voters’ minds. That also includes growing sidewalk encampments of the unhoused, paired with public drug consumption.

During the pandemic, the rate of shoplifting and commercial burglaries skyrocketed, especially in Los Angeles, Alameda, San Mateo and Sacramento counties. Statewide, the institute found that reported shoplifting of merchandise worth up to $950 soared 28% over the past five years. That’s the highest observed level since 2000.

Combining shoplifting with commercial burglaries, the institute’s researchers found that total reported thefts were 18% higher than in 2019.

“California voters have spoken with a clear voice on the triple epidemics of retail theft, homelessness and fatal drug overdoses plaguing our state,” said San Jose Mayor Matt Mahan. “In supporting Proposition 36, they said yes to treatment. They said yes to accountability. And they said yes to putting common sense before partisanship, so we can stop the suffering in our communities.”

Californians still want rehabilitation for prisoners

The measure’s opponents say that Prop. 36 was a clever way to reintroduce the war on drugs in a way that will be palatable to voters in 2024. They argue that no studies on criminal justice or homelessness support the idea that harsher punishment — or the threat of harsher punishment — prevents crime or gets people off the street.

Prop. 36 will expend hundreds of millions of dollars in court and prison costs, they say, without measurably reducing crime or poverty.

“We are aware that there’s been a shift in terms of the vibe around criminal legal reform,” said Loyola Law School professor Priscilla Ocen, a former special assistant attorney general at the California Department of Justice.

“I don’t agree with the premise that California is swinging more rightward when it comes to the bad old days of mass incarceration,” she said. “I think on certain issues, yes, the electorate is frustrated with feelings of insecurity — despite the fact that those feelings are often not grounded in data in terms of your likelihood of being victimized, either by a property crime or a crime against a person.”

I’d agree the media–even before social media–has influenced the response to crime. Hollywood tells us that police solve 90% of the crimes. Reality tells us they solve 13.2% (in 2022). US population grew 42% between 1982 and 2017. Spending on policing grew 187%. In the last 50 years US incarceration grew from about average to–now–roughly five times the world’s per-capita average. That’s seven times more than Canada or France, and they have lower crime rates. One significant difference: the US has more than a half million medical bankruptcies annually. Canada and France don’t have medical bankruptcies. Could making a half million people financially desperate motivate more of them to take desperate measures, like crime? Gosh, I wonder.