By Scott Thomas Anderson

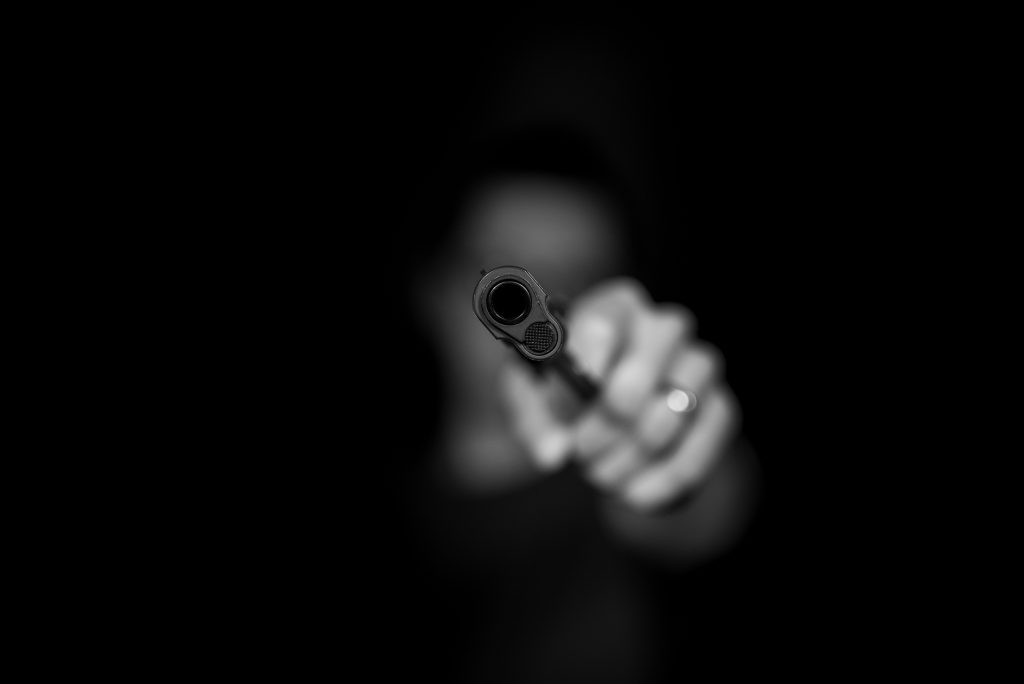

On an April afternoon, a team of CHP officers confronted a volatile man they’d been tailing – and they did it at a west Roseville park where men, women and children were going about their day in the mild spring weather.

These officers suspected the man was a hot-headed shooter who tried to harm a random motorist just weeks before. As they prepared to engage him, the team had unobstructed views to young athletes on the fields and in batting cages. They also knew that they were staked-out roughly 300 feet away from a public library. And even a quick inspection of the grounds would have clocked the highly-trafficked footpaths behind a creek to the rear of the baseball diamonds.

Despite knowing exactly where their target lived – less than two miles from the recreation area where they were watching him – and despite one officer present having serious reservations about all the innocent faces he was seeing in the park, the task force went straight at their dangerous target.

If Eric Abril had meekly surrendered, then it’s likely no one would have noticed anything unusual that day.

But he didn’t.

Instead, Abril turned Mahany Park’s lawns into a temporary war zone.

The thunderous firefight that broke out caused residents to dive down for their lives, 33 children inside the library to shelter in place, and a married couple enjoying the fresh air to get pulled into a nightmare – an ordeal that one would not survive.

Adding to Roseville’s communal trauma, in the aftermath, Abril – now charged with taking hostages and shooting multiple victims – escaped from the Sheriff’s custody, sparking an intense two-day manhunt as he stalked through brushy undergrowth behind numerous peoples’ homes.

Law enforcement agencies have been mum about how Abril first came on their radar and almost entirely silent about how things went so wrong in Mahany Park on April 6, 2023. Now, thanks to a lengthy preliminary hearing, many of the details have come to light. They reveal a chain of decision-making by the California Highway Patrol that may be scrutinized for years to come. They also expose misreporting by some Sacramento news agencies, specifically those who suggested that a homicide victim was killed by police bullets when all evidence and witness statements indicate a merciless execution at the hands of Abril.

The suspect

According to testimony, the bedlam had its roots in an apparent road rage incident in Sacramento County.

On Feb. 16, 2023, California Highway Patrol Detective Leo Smith was called to the scene of a freeway shooting not far from 12th Street. Smith later recalled in court that the victim had been fired at from a dark-colored SUV, a bullet piercing their right rear door. Smith eventually found a 10mm round inside the cab and then a shell casing on the freeway.

As the investigation progressed, Smith used various pieces of video evidence to determine that Abril, 35, was his shooter. Abril was living on Burnt Cedar Way in Roseville at the time. Smith was granted a court order to slip a GPS tracker on Abril’s brown Toyota Sequoia. He also had a warrant to search Abril’s home and person.

April 6 was the day that Smith and other members of CHP’s Investigative Services Unit decided to make that happen. A number of the detectives – testimony suggest around 20 – met at 8 a.m. to carry out the operation. At that point, they had been monitoring Abril’s movements long enough to know that he had a routine of walking his two dogs in Mahany Park.

Smith testified that a decision was made to have some of the CHP officers confront Abril at Mahany while others searched his house at the same moment.

“I had authored an operation plan that’s preapproved by our management,” Smith acknowledged on the stand. “When we met that morning, I’d gone over the operational plan, and we had discussed the operation itself.”

Between seven and ten members of the team headed for West Roseville at 8:40 a.m. They were soon waiting in unmarked vehicles in front of Mahany Park or taking up different positions outside with their badges concealed. A little past noon, they spotted Abril. He was wearing a long black jacket, khaki pants and “sturdy shoes.” They watched their suspect turn his truck engine off at the other side of the dog park near the baseball fields. Abril got out and played with his canines for a while. When CHP noticed him walking the pets back towards his Toyota, they prepared to make their move.

Abril was getting close enough to see that cars were blocking his truck and a man wearing a black baseball cap emblazoned with “police” was heading his way. That man was Leo Smith, who later detailed in court that also wore a dark hoodie and a vest on that said ‘police’ in bright yellow letters. Other detectives in dark clothes were moving towards Abril, too, as well as one CHP officer in full uniform – Officer Canela.

“I yelled at him, ‘Police. Hands up. Get down on the floor,’” Smith recalled. “He put his hands up and said, ‘Wait, wait, wait.’ And he looked to his left – and then to took off running.”

Shots, smoke and diving civilians

When the detective pulled his Smith & Wesson 40-caliber and ordered Abril to surrender, the suspect had dropped his dog leases to bolt across an uneven span of grass and then by some maple trees. Other officers would remember Abril’s confused dogs running after him. Smith re-holstered his gun and charged in pursuit. The two were dashing towards a concession stand when Smith heard another voice shouting, “Gun! Gun! Gun!”

The person yelling that was Sacramento Senior Deputy Probation officer Tyson Becker. A 26-year veteran, Becker belonged to a multi-agency vehicle theft task force under the directed of CHP. Though not with state police, he had joined CHP’s team that morning to lend some extra backup. Up until that moment, Becker had been mulling around, undercover, in the park. He was wearing a badge on a chain around his neck, which he had hidden under his blue hoodie. Before CHP had even confronted Abril, Becker was worried about the situation.

“And why were you concerned?” Deputy District Attorney David Tellman asked him during the court hearing.

“We were doing a search warrant for a subject who was possibly involved in a shooting,” Becker pointed out. “So, just out of safety to the other people. That was my concern.”

When Becker saw Abril barreling in his direction, he pulled his badge from under his shirt and surveyed the circumstances. In addition to “several children and some adults” on the baseball fields, he saw “numerous people at the dog park as well.”

And then his fears came to fruition.

Becker testified that, when Abril closed in within 10 yards, the suspect reached over to the right side of his hip and whipped a semi-automatic pistol out from under his shirt. Becker was shouting “gun!” as he drew a beat on Abril with his own pistol. But – Becker knew he shouldn’t fire.

“I observed two kids right in – right in the line of sight,” Becker remembered. “At that point, I turned around and I ran as fast as I could to the ‘A’ concession stand … I heard multiple gunshots.”

According to Leo Smith’s testimony, those shots were Abril trying to kill Becker.

“What did you see happen next?” Tellman inquired.

“I saw Tyson [Becker] go down,” Smith replied. “I thought Tyson had been shot.”

Becker would recount that instance as a blur, his head on the ground as dust was exploding off the dirt around him from incoming fire.

Smith started shooting at Abril. The suspect turned and fired rounds back at him.

“I heard bullets whizzing by my head,” Smith told the court. “He continued to run, firing behind him – firing towards our direction … He continued to run through the center of the two ballparks there towards the grass area.”

As he shot, Smith thought he’d hit Abril, but he wasn’t sure. But then the detective stopped pulling his trigger.

“The batting cages had a couple of young boys in it,” Smith testified, choking up a little. “I wasn’t going to continue shooting.”

“And as the defendant got to the batting cages, do you remember hearing anyone behind you shoot?” Tellman asked.

“No,” Smith responded, “there was not shooting then.”

According to Roseville Police Detective Christopher Guild, the gunfight started right as a batting coach named Cody Baron was finishing lessons with one student and beginning lessons with another. Baron, the two kids and one of their parents, were all forced to take cover. Baron made it to a dug out with one of his clients and they were laying on the ground. One of the CHP officers was not so lucky – he got shot in the exchange.

Smith watched Abril escape into a low, wooded creek-way chocked in berry vines, cattails and canyon oaks. The suspect ran into it, with his gun out, just 200 free away from an elaborate children’s playground behind the library. Smith cleared Baron and the young people out of the batting cages before taking up a position behind a pole. He could see Abril’s two dogs circling the brush. Then gunfire started blazing out from the oak branches. Puffs of dirt were exploding around Smith. He heard the whale of emergency sirens getting louder. A Roseville police cruiser tore up near him, its officers shouting for him to get their vehicle.

A Roseville officer who was driving to a different part of the maelstrom was Pavindeep Hayer. He’d been on patrol when the incident started and raced towards Mahany Park. Hayer pulled down a gravel road that was south of the creek. Hayer testified that he heard bullets ringing as he got out. Nearby, another member of Roseville PD – Officer Strickland – was firing in Abril’s direction. Hayer was trained to operate police drones. He quickly got one up into the air. The view wasn’t good.

“The suspect was holding a female on top of him,” Hayer testified, “and was – eventually I saw he was holding a firearm to her head.”

Hostages

James and Patricia MacEgan were on a walk together that afternoon. James was 72, Patricia, 71. They were strolling down a footpath that went through the greenway below Mahany’s baseball fields. They saw joggers pass by them. A dog-walker was going down the trail. The area was peaceful. At a certain point, the MacEgans reached a creek that was too wide to cross, so they turned around and headed back. Suddenly the air was exploding with gun shots. Patricia would later describe it as sounding like fireworks.

James told Patricia that they needed to get on the ground. They both hit the deck on their stomachs. Patricia heard what she thought were bullets whizzing past her. All at once, there was a lull in the cacophony of noises. Patricia asked James if he thought they’d heard gunshots. He told her he did, and that she needed to stay down.

Around that time, according to testimony, Patricia noticed a clean-shaven man “run from the paved area towards some trees.”

Alana Gurchow, a Placer County DA Investigator who interviewed Patricia MacEgan in the hospital, describe in court what happened to the MacEgans next.

“As they laid there, they just were trying to figure out what was going on,” Gurchow explained. And then [Patricia] heard some splashing in the creek behind her … She heard something to the of effect of, ‘Keep your head down, your hands up.’”

“And did she describe how close the person was who was yelling this?” asked prosecutor Kalin Everett.

“Very close,” Gurchow replied. “She complied.”

“Meaning she kept her head down?” the prosecutor clarified.

“Yes,” Gurchow said. “She stated that her husband peeked basically from side to side to see who was yelling … her face was on the ground, but her eyes – she could see with her eyes.”

“After she saw her husband move his head side to side, what happened next?”

“She heard a single gunshot,” Gurchow responded. “She said it was very loud and made her ears ring. It was so close she could smell the gun powder … There [had been] a large flash of light … She heard her husband say ‘Ow.’ She asked him if he was okay. He said, ‘No.’ And she saw him start to fade.”

James would never open his eyes again.

“What did Ms. MacEgan tell you happened next?”

“She felt one hand on each of her ankles, and then she was dragged into the creek,” the investigator testified. “She felt a gun on her head, neck and temple, and she was told to call the police – or, I believe, it was 911 … he placed her directly on top of him. She stated that he used her as a shield.”

It had seemed to Patricia that the attacker was young, lean and strong: He was able to easily move her body around. The assailant again ordered her to call 911 with her phone, adding that she needed to put the device on speaker-mode. Patricia did that. Abril began telling her exactly what to say to the dispatcher, even though she thought the dispatcher could probably hear him clearly.

“The suspect wanted the drones, helicopters and police to go away,” Gurchow remembered. “And that, if they did not go away, he was going to shoot her.”

To prove his point, Abril lowered his pistol from Patricia’s head, placed it on her right arm – and then pulled the trigger at point blank range.

Patricia would later tell police “the pain was essentially unbearable.”

A drone picked up blood going through Patricia’s shirt.

“Did she describe that she thought she was going to die in the creek?” Everett asked during the hearing.

“Yes,” Gurchow said.

“Did she describe to you that she, in fact, prayed, thinking this was going to be her final moments?”

“She said she did, over and over.”

Patricia had been exhausted. She’d lost the use of her arm. According to her account, Abril pulled her through the creek before forcing her onto a bank. Patricia fell flat on her face. She was in the mud. At one point, Abril pulled her shirt off and put it over Patricia’s head.

Just then – police officers rescued her.

Everett had another question for the DA Investigator before she left the stand.

“And when you played part of the [911 call] for Ms. MacEgan, was she able to recall something the suspect had said to her while he was holding her in the creek with a gun to her head?

“Yes,” Gurchow replied. “He stated that he thought her husband was a cop.”

Post-script: Patricia MacEgan has filed a wrongful death suit against the California Highway Patrol. The CHP’s official position is that it is immune from liability for any injuries caused by someone resisting arrest.

Trying again point being the CHP screwed the pooch