A rare mix of big strike wins, broad public support and a labor-friendly economy could drive union membership growth.

By Mark Kreidler, Capital & Main

This story is produced by the award-winning journalism nonprofit Capital & Main and co-published here with permission.

The news on union organizing in 2023 could be confusing or even contradictory. The year was marked by high-profile union wins across multiple and varied employment sectors, yet federal statistics found American unionization rates falling to their lowest levels since comparable data began being kept 40 years ago.

That darker second reality might, to some, appear to invalidate the first.

Say the experts: Not so fast.

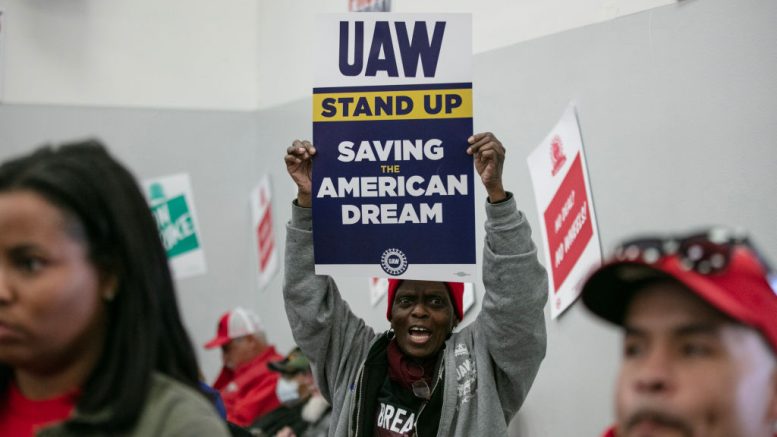

Extraordinarily high public support for unions, combined with successful strikes in such disparate areas as Hollywood entertainment and Detroit automaking, has swung the organizing pendulum at least slightly in the unions’ favor. It may just take a while for that shift to become more visible.

Perhaps most importantly, workers hold a stronger position in the economy right now. “This is the first time in a long time that we’ve seen this big set of economic factors that are really increasing the power of the labor unions at the expense of employers,” Michelle Kaminski, a professor and labor expert at Michigan State University, told Capital & Main earlier this year. “This is the strongest leaning of the economy in that direction in some time — in recent memory, I would say.”

The combination of inflation and a tight job market is at work here. Not only did the rising cost of living lead workers to demand significant wage increases, but fewer workers were available in the job market generally. Companies that might normally stall contract negotiations in hopes that union workers would become disillusioned and quit couldn’t as easily replace them in 2023, and that dampened the effect of a tactic employers have successfully used for decades.

* * *

While the percentage of all American workers who are unionized dipped to 10.1% in 2022, the last year for which data are available, the raw number of union workers actually rose by about 275,000, or nearly 2%. The overall unionization rate dropped in part because so many jobs were added to the U.S. economy, and most of those weren’t union positions — but that same job growth has pressured employers to hang on to the workers they already have.

Kaminski also noted the pandemic’s role in the heightened profile of unions. Workers in such sectors as health care, agriculture, grocery and transportation were declared essential and made to work through some of the worst of COVID’s ravages, yet their wages and benefits often remained at unsustainable levels.

“There were huge demands on workers in areas like health care and grocery to put in extra hours and keep showing up in person, but they didn’t feel like they were being compensated as though they were ‘essential,’” Kaminski said. “All this has shifted the balance in favor of unions, because employees were feeling very strongly that they needed to be treated better.”

In 2023, many of those unions came through. About 70,000 Kaiser Permanente workers won pay raises totaling 21% by 2027. The United Auto Workers secured raises of at least 25% over four and a half years from the Big Three automakers, then began organizing at nonunion companies like Tesla and Toyota. The Teamsters and UPS negotiated a five-year contract with substantial wage gains and safety enhancements for more than 340,000 workers.

Union success in Hollywood didn’t hurt. Both the Writers Guild of the America and the actors union SAG-AFTRA achieved significant gains and protections after protracted strikes against the Hollywood corporations that negotiate as a behemoth collective. Poll after poll showed much more support for the striking workers than for their employers.

* * *

Will that momentum pay off in increased unionization rates? We’ve not yet seen the numbers for 2023, with the Bureau of Labor Statistics’ report likely to arrive in late January. It also has to be noted that despite a year of hard-fought gains at several union-represented workplaces, employers in general retain a commanding advantage in defeating union activity. Outdated federal labor laws and decades of pro-employer court rulings have allowed companies to openly interfere with organizing efforts — or decline to negotiate meaningfully once a union has formed.

But momentum for unions doesn’t always follow a smooth trajectory, either upward or downward. Those who have long studied unions say that growth sometimes takes place in huge waves, such as the dramatic spike in the Depression-era 1930s. Such a wave could be building now.

It was not until December of 2021 that a single Starbucks store finally voted to unionize. Two years later, that count is up to 380 stores, according to the organizing group Starbucks Workers United.

“Right now, unions are the only way that workers have a chance to get ahead of some of the changing conditions in the workforce, including the use of AI and the effects of climate change on workers,” said Harvard labor expert Sharon Block. “That could change the politics of some people who aren’t currently in unions.” This year, the country may well have taken a step in that direction.

Copyright 2023 Capital & Main

Be the first to comment on "Are unions about to reverse 40 years of decline?"