After the richest men in California temporarily shut-down a crusading Sacramento journalist, he went on to be a force within the region’s most intriguing press club

By Kevin Taylor

This Land is Your Land. This Land is My Land.

The Bohemian Club formed in the late winter of 1872, 150 years ago, to promote good fellowship and intellectual intercourse among journalists. Comfortable reading rooms in its San Francisco location would be secured where files of the leading newspapers, magazines and journals were kept. It would be a place of resort for members in leisure hours. Early comrades affiliated with newspapers included Sands Forman and Edward H. Hamilton of The Examiner; Thomas Newcomb of The Call; Fred Somers of The Argonaut; Daniel O’Connell, who wrote for The Bulletin and founded the Illustrated Bohemian; Crocker family nemesis Ambrose Bierce of The Wasp, whose “Prattle” was the most vicious and vindictive newspaper column in the city; and Henry George, scholar, writer, social and political activist, first as a founding editor of The Sacramento Reporter, then as a managing editor of The San Francisco Chronicle and The Evening Post.

It was advertised in local papers that professional journalists were eligible for active membership; artists, actors, essayists, writers of books, poets and dramatic authors, could be honorary members after the payment of certain fees. They voted to keep out rich men, publishers, and other natural enemies of the Muse.

Public demonstrations on behalf of any political party or religious organization was strictly prohibited.

To quiet objections to the dreadful word “bohemian,” the definition was adroitly altered by club founder O’Connell from a stringy haired, scuzzy, penniless gypsy, who paints in frosty attics, sleeps on sofas, drinks cheap wine and smells like a billy goat to “a man of genius who refuses to cramp his life in the Chinese shoe of conventionality, whose purse is ever at the disposal of his friends, and who lives generously, gaily, carefree, and as far from the sordid, scheming world of respectability as the south pole is from the north.”

The owl, the revered bird of wisdom, was made the sacred symbol of the organization. St. John Nepomuck, a Czechoslovakian from geographic Bohemia, who died rather than tell a woman’s secret, became the club’s adopted good saint. “Weaving Spiders Come Not Here,” taken from A Midsummer Night’s Dream, became the club motto.

The idea of a press club evolved quickly to include into the fold the city’s artists as fully fledged and pledged members. They were selected from gentlemen who possessed artistic talents and who wanted to promote innovations in the Seven Arts (architecture, sculpture, painting, music, poetry, dance, and theater). Knowledge and appreciation of “polite literature,” science and the fine arts became an absolute prerequisite to all members. The Bohemians lofty goals included “the collection and preservation of records, mementos and archives illustrating the progress of literature, and science and art of the Pacific coast, and calculated to perpetuate the memory of those who have been or shall be instrumental in promoting such progress.”

A more perfect union was established.

Zealous painters were easily corralled; they had recently formed and founded the San Francisco Art Association. (They would later set up camp in the same building as the Bohemians). These local artists, under the spell of French open-air techniques and James McNeil Whistler, took up the garret life. They were welcomed with open arms. Clubbing with the bachelor Bohemian artists in a dingy studio on the top floor of some sinister looking house in the Latin Quarter or the Barbary Coast was a barbarically splendid adventure not to be missed.

The flagship of the city’s flowering literary scene was then found at the Golden Era newspaper, edited by Bret Harte. Its featured writers included “Pfaffian” transplants Artemus Ward, Fitz Hugh Ludlow, Charles Henry Webb, Adah Issacs Menken and the reigning Queen of Bohemia herself, Ada Clare. They were America’s first self-identified Bohemians who hung out at Pfaff’s beer cellar in Manhattan. The great bard Walt Whitman was part of that historic literary gang. Other contributors included Ina Coolbrith, California’s first poet laureate; gay travel writer Charles Warren Stoddard; Cincinnatus Hiner Miller, aka Joaquin Miller, “the Poet of the Sierras;” and Samuel Clemons, who adopted the pen name Mark Twain during his time working for The Sacramento Union.

The Bohemian Club was quick to court this Golden gaggle and coronated Harte, Coolbrith, Miller and Twain as honorary members. Robert Louis Stevenson, Oscar Wilde and Rudyard Kipling were early guests.

The formal opening of the club was on April 14th, 1872. It was a true feast—a feast for the eyes, the ears, the soul and the “courser nature.” In accordance with Bohemian conviviality and customs, there was nothing actually truly formal in the whole reception. Rich beverages prepared homeopathically for the occasion were dispensed. They first drank to the city of Prague, capital of geographic Bohemia. General W.H.L Barnes gave a humorous history of the “Amador War” at the quartz mines in Amador County. J.G. Then, Eastman argued that a gentlemen’s club was a religious institution, which brought down the house in a burst of applause. Colonel Cremony spun a yarn about Cochise–his “foster brother”–who he described as a gentle Apache yet a dangerous Bohemian. Newly elected President Thomas Newcomb sang a song of Bohemia. The whole company cheerfully joined in. It was followed by music on the piano—a selection from the “Bohemian Girl.” Robert Craig, an invited guest, gave a capital recitation from Pickwick Papers.

Ladies present wanted to join the club.

During one of the preliminary meetings the question of admitting lady members was broached, but was met with little favor, and the matter was dropped. They envisioned women of ill repute being introduced by a side door who would then “pay a conspicuous part in the after proceedings.” Ida Coolbrith, later the club librarian, would be one of only four women admitted into the elite club in its entire 150-year history.

According to declarations in the club annals these genteel Bohemians were nothing less than prophets and reformers, the visionaries of a great movement, “the Moses & Co., as it were, who led the art tribes out of the Egyptian land of Commerce into the promised land of Bohemia.” The club members were second generation Californians, sons of frontiersmen, argonauts, self-made men and some of the most successful capitalists the country would ever create. These early pioneers built a solid and impressive infrastructure, lured investors, industries and government grants to the Golden State, began the process of building cultural institutions, and successfully campaigned for California to enter the Union as a free state.

But it would fall on these Bohemians, a class of men with plenty of leisure for thought and culture, to build not just a city, but an Athens, a Flanders, or a Rome … with great museums, libraries and universities; noble literature and honorable newspapers; magnificent theaters and opera houses; parks and pleasure gardens. They saw rays of brilliance among their numbers and in the Northern California ecosystems that needed nourishing and nurturing. They wanted to keep the talented artists and scholars living in San Francisco from moving to older and larger cities to find wealth and distinction.

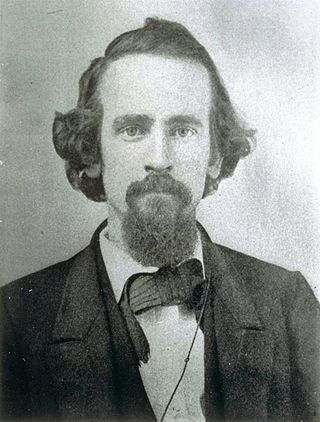

Henry George

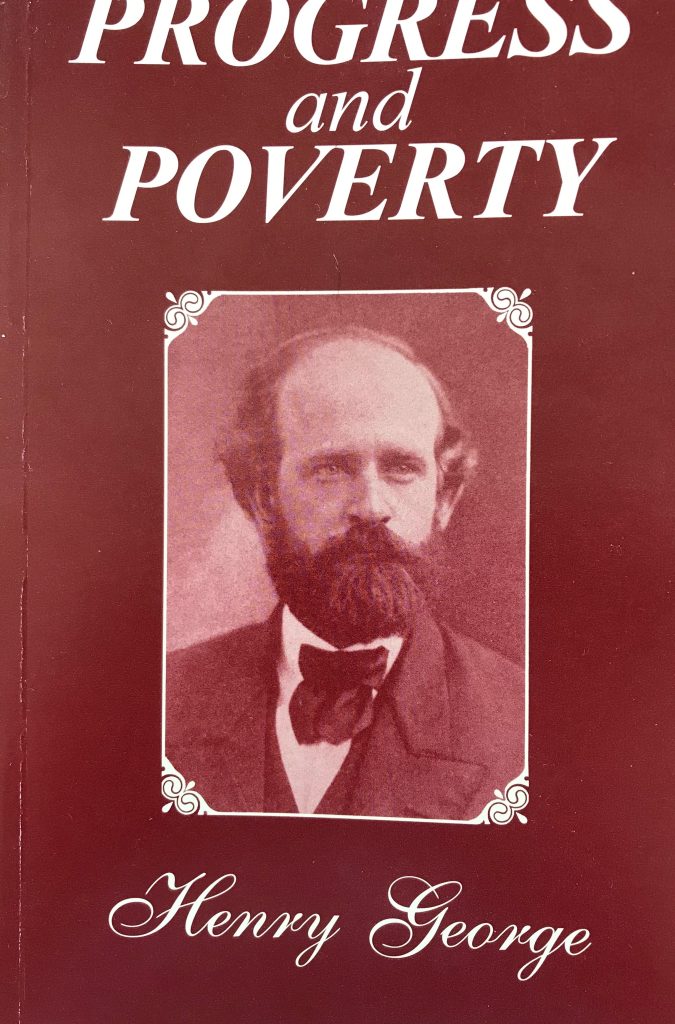

The biggest star to come out of the early Bohemian Club years was, of course, the charismatic political economist and journalist, who sparked several Progressive Era reform movements, Henry George. Some historians consider him to be the most popular American figure of the 19th century after Mark Twain and Thomas Edison. George authored the second biggest seller of the century after the Bible, Progress and Poverty. Months before the Bohemian Club formed, George founded and edited The Daily Evening Post, which quickly boasted the highest circulation in the city. It was while managing and editing The Post, and palling with fellow Bohemians, that George advanced his ideas, and conceived and mapped out his life’s work.

George watched the evolution of the city of San Francisco that transpired at breakneck speeds in the 1860s and 70s. He arrived in 1858 at age 19, to find a provincial, multicultural community of transplants that possessed a high level of cosmopolitanism with “a certain freedom and breadth of common thought and feeling, natural to a community made up from so many different sources.” On the American frontier, HG observed, there was neither great wealth nor grinding poverty. All men worked hard and were rewarded with material blessings in approximately equal proportion. He saw a relatively high standard of wages and of comfort. He saw a populace that expressed, “a feeling of personal independence and equality, a general hopefulness and self-reliance, and a certain large-heartedness and openhandedness which were born of the comparative evenness with which property was distributed …”

Yet as industry progressed and the city rapidly rose, so too did the disparity of income and opportunity. Far from alleviating human want, material progress was augmenting it.

George attributed the swift changes on the West Coast, to a large degree, on the completion of the Transcontinental Railroad, which he considered, the “greatest work of the age,” acknowledging that it didn’t merely open a new route across the continent, but was the means of converting a wilderness into an empire in less time than many of the cathedrals and palaces of Europe were built.

George watched the rise of the Big Four from the Central Pacific Railroad Company – Collis Huntington, Mark Hopkins, Leland Stanford and Charles Crocker–who were controlling more capital and employing more men than any of the great eastern railroads. Unlike most journalists who railed at the “robber barons” painting them as rapacious, greedy vultures, Henry’s criticisms concerned the system that gave them so much wealth and power. The Pacific Railway Act, signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 1, 1862, gave directly, without the intervention of States, to the Central and the Union Pacific companies, ten sections of land per mile (at that time the largest amount ever granted), and $16,000 per mile in bonds. In 1864 this grant was doubled, making it twenty sections or 12,800 acres per mile, and at the same time the bonded subsidy was tripled for the mountain districts of the Sierras.

H.G. reported that because of these obscene land grants, the Central and Southern Pacific Railroad Corporations were the largest landowners in California, in all controlling some 4 million acres in several states. In addition to their company land, these franchises owned considerable tracts in their own name. The Big Four was granted by proclamation vast timberlands, large amounts of fertile agricultural lands in California and along the Nevada river bottoms, and millions of acres of the best grazing lands in the sagebrush plains of Nevada and Utah. Thousands of acres had enormous value from the coal, salt, iron, lead, copper and other minerals they contained.

When George editorialized against the CPRR in The Sacramento Reporter, the Big Four purchased the publication and closed it.

George saw, in these early years, the development of the newspaper in a direction which made it less and less the exponent of ideas and advocate of principles, and more and more a machine for money-making espousing sensationalism and yellow journalism and trumpeting capitalist ventures.

Henry George watched the emergence of a political movement growing from and taking advantage of widespread discontent after the Panic of 1873 and a worldwide economic recession. Bank runs and bank failures were widespread and triggered commercial bankruptcies. Inflation and unemployment became a severe drag on the economy. This epic downturn is now referred by historians as “the Long Depression.” While the lower classes struggled, George observed the Big Four building the largest mansions ever built within the city limits. Henry wrote:

When, under institutions that proclaim equality, masses of men, whose ambitions and tastes are aroused only to be crucified, find it a hard, bitter, degrading struggle even to live, is it to be expected that the sight of other men rolling in their millions will not excite discontent? And, when discontented men have votes, is it to be expected that the demagogue will not appeal to the discontent, for the sake of the votes?

Rabble-rouser and demagogue Denis Kearney, organized the desperate masses in San Francisco, helped form the Workingmen’s Party, and took political power in the city and the state in the late 1870s. The party took particular aim against cheap Chinese immigrant labor and the Central Pacific Railroad which employed them. They formed the California Railroad Commission that would oversee the activities of the Central and Pacific Railroad companies. Their new constitution was, however, destitute of any shadow of reform which would lessen social inequalities or purify politics, according to Henry George. They failed to recognize that social and political evils arise from wrong systems, not the wickedness of individuals or classes.

People were so utterly disgusted with the workings and corruptions of old parties and the oligarchs they would have, “endorsed imperialism or Mormonism or spiritualism or vegetarianism,” wrote George.

H.G. thought that the crowding of people into immense cities, the aggregation of wealth into large lumps, and the marshalling of men into big gangs under the control of the great “captains of industry,” didn’t foster personal independence — “the basis of all virtues.” The rich were getting richer, the poor more desperate and shut out. But George believed that it was the controlling of the land by these oligarchs that was the true source of society’s ills and punishing inequities.

The path of San Francisco was sure to follow that same course as every other big city like New York which, George felt, was “ruled and robbed by thieves, loafers and brothel-keepers; nursing a race of savages fiercer and meaner than any who ever shrieked a war-whoop on the plains.”

Why, George questioned, in the midst of ever-growing plenty, does poverty persist and indeed flourish? Why, “amid the greatest accumulations of wealth, do men die of starvation, and puny infants suckle dry breasts?” This paradox, while worldwide, was and is nowhere more evident than in the United States, where “almshouses and prisons are as surely the marks of material progress as are costly dwellings, rich warehouses, and magnificent churches.” With increases of productive power and invention came exponentially more human deprivation. George noted, “want and insanity and criminality are increasing, marriages are decreasing, and the struggle for existence becomes not less, but more and more intense.”

It was these burning questions that George wrestled with. During leaner times in his life he was forced to become a beggar in the streets to feed his family. Like Buddha under the Bodhi Tree, George the journalist, under the California redwoods, became enlightened. A simple solution became abundantly clear and obvious.

Under the Redwood Trees

The board of directors at the Bohemian Club, under Thomas Newcomb’s presidency, were entirely in sympathy with those members who lived by their wits and spent the money they earned, and all they could borrow, without a thought of paying their dues. There was, however, much difficulty in devising means to furnish the rooms and to defray expenses. The original members had been enforcing Bohemian policies that made it, “easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for a rich man to enter the Kingdom of Bohemia.” It became apparent that the possession of talent, without money, would not support the club. They reached a conundrum. If they refuse to remit the dues of those who couldn’t pay, Bohemians who furnished the medley of wit and humor, music and song, they would deprive the club of its chief glory. If they continued to treat them generously, the club will soon be bankrupt. It was decided that they would invite an element to join the club which the majority of the members held in contempt, namely, men with money.

Within five years after the foundation, the Bohemian Club included among its members all the most eminent men of the State. In 1877, Col. C.F. Crocker, aged 22, future vice-president of the Southern Pacific Railroad Company, regent of the University of California, president of the California Academy of Sciences, and trustee of Stanford University, would join the Bohemians. His younger brothers, a couple of cousins and his son would follow.

In 1878, English stage actor, writer, entomologist and one time club president Henry Edwards decided to accept an engagement in the stock company of Wallack’s Theatre in New York. It was determined that a unique farewell entertainment should be given. One member suggested a “Nautical Jinks,” another a picnic on the Lagunitas. They landed on a “Jinks in the Redwoods” and selecting Camp Taylor, on Paper Mill Creek, as the scene of this extraordinary noctambulation. Henry Edwards was made Sire of the occasion, and Amy Crocker’s close friend Frank Unger was the Musical Sire.

It is Dan O’Connell who is credited with inventing a peculiarly hilarious and detonating species of amusement known as the “Jinks,” which were dramatizations evolved out of the mutual joshing of fellow drinkers, of humorous and sentimental recitations, of play-making and music-making under the influence of libations. There were the “Low Jinks” comic skits which were more improvised than the “High Jinks” performances which were dramatic, staged and rehearsed and over the years became complex, fantastic productions.

At the Jinks in the Redwoods, nearly 100 men spent the afternoon roaming the forest, frolicking in the stream or idling in the sun. There were swimming meets. There was pearl-diving. The artists sketched, the poets dreamed, philosophers meditated, smokers smoked. They gathered at twilight around the campfire. The trees were hung with Chinese lanterns. Lights twinkled through trees and bushes like a swarm of fireflies. Artist Julian Rix was the barkeep. Henry George recited a poem and performed practical jokes on his fellow campers. There were stag dances on the grand platform by the brook side. They sang song after song, gave recitations, speeches and toasts with well-buttered compliments. They told droll stories. It was fairyland at midnight. The owls hooted and the crickets cried, and one by one the revelers withdrew.

The forest was majestic and beguiling.

Coast redwoods grow higher than the giant sequoia and can survive up to 1,800 years. Mammoth in diameter and height, the California redwoods attain an average height of 330 ft. Author John Steinbeck found them awe-inspiring “ambassadors from another time.” Ernest Lawrence, the Nobel Prize winning physicist and club member wrote:

To all true bohemians this Grove is a shrine, an enchanted forest. Around and about it, trees, or generations, have spun a web of sentiment and tradition so rich and deep as to be almost tangible. On its leafy carpet have trod the feet of men who have drunk more deeply of friendships than were possible on any other place on earth.

A wonderful time was had by all.

It was decided that the Bohemians would congregate in the redwoods midsummer every year, to camp and hold forest High and Low Jinks performances.

The Jinks plays were replete with mythologies and ritual enactments and included blockbusters like The Man in the Forest, a Legend of the Tribe; the Druid/Buddha/Hamadryad & Gypsy Jinks; The Sons of Baldur; The Quest of the Gorgon; and the famous (some say infamous) Cremation of Care, which became a ceremony that kicked off the larger plays and events every year since it was created in 1881 by Fred Somers. James Bowman was the Sire and Frank Unger was again the Musical Sire.

Derived from Druid rites, medieval Christian liturgy, the Book of Common Prayer, Shakespearean drama and nineteenth-century American lodge rites, what transpires during the Cremation of Care is an epic battle between Brotherly Love and Christianity and paganism. At sundown on the first Saturday of their encampment, a procession of men in hoods and robes accompany a handful of pall-bearers as they carry an open coffin containing a black muslin covered wooden skeleton. They burn this effigy of “Dull Care” at the bottom of a forty foot stone owl.

The bohemian campers rationale is that they carry the cares and woes of the world around on their shoulders and they need a symbolic ritual in order to release its burden and enjoy their retreat. The Cremation of Care, which kicks off midsummer events every year, prepares the way for the “Spirit of Bohemia” to refresh its affiliates and open them up to transcendental experiences.

In the afterglow of their first gathering at the enchanted forest, the Bohemians basked over the utopia that they created. They had feared that the co-mingling of the rich and the poor, the artists and the capitalists, would destroy the club. Instead they successfully created a classless society of spiritual brothers. No lines were drawn on how a man earned his living, or how much or how little money he had or owed. “For, since the hour when the Club was founded to the present day, its peculiar spirit of Bohemianism has never been confined to the professional artist, literary man or musician. Some of the very best Bohemians have been capitalists, merchants, lawyers, doctors, aye, even men about town– gentlemen who have never painted a picture, played a musical instrument nor written for the newspapers,” according to club annals.

It was at first a perfect marriage of wealthy businessmen who were very much patrons of the arts and consumers of exotic commodities and racy leisure activities, and, exquisitely talented painters, musicians and writers who were poor but congenial, witty and entertaining. Together they were an idealistic band of Bohemians who waved a Gospel of the Moment/Brotherly Love banner. The club developed a latter-day version of Europe’s court patronage system. The starving garret artists got some financial freedom while the railroad tycoons could soften their philistine edges. It was a social arrangement reminiscent of the Medici.

In time the Bohemian Club followed the same course as the city, the rich were getting richer and the poor were slowly getting shut out.

The Swallowtails

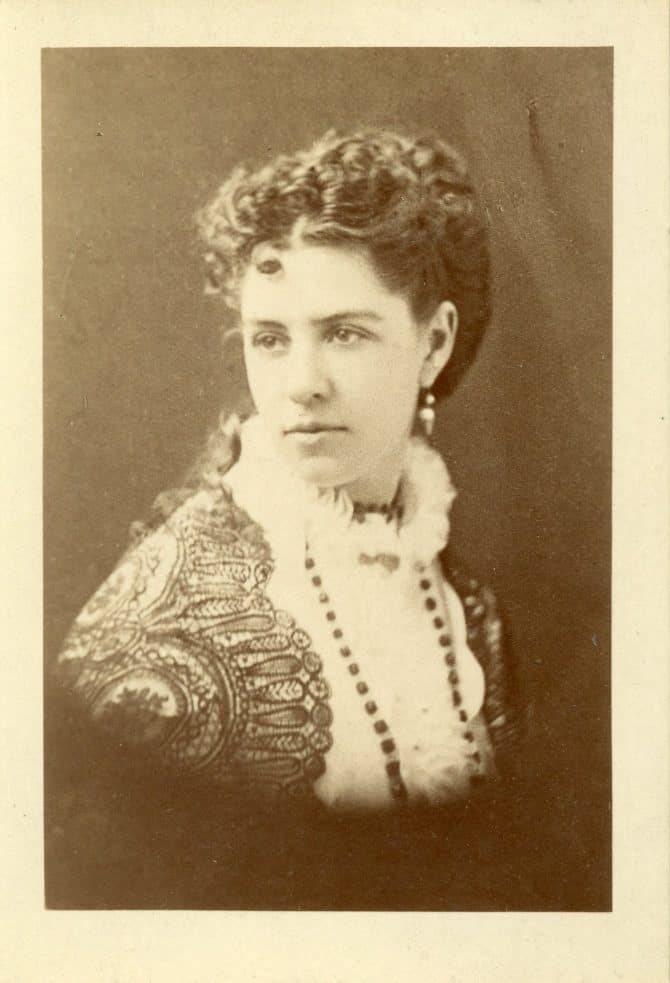

A year after the first midsummer encampment, Frank Unger, the longest and dearest man-friend of Sacramento’s renegade writer and socialite Amy Crocker, was the Sire of a Ladies’ High Jinks. The innocuous invitation informed the bachelors and Benedicks of Bohemia that the romantically available ladies that were invited would be surfeited with complimentary sweets and that the subject of the Jinks would be “Bric-a-Brac.” A post scriptum notified the brethren that “no swallow tails shall be worn.” This remark was in reality a gunshot that waged a war between the haves and the have nots–those who had artistic talents and those who didn’t.

On one side was arrayed the promoters and founders of the Club, the writers, actors and painters, the clever Bohemians with brains and an ingenious faculty for sociability. On the other side arrayed arrogant wealth and fashion, the weaving spiders of commerce, men who entered the Club through the broad gateway of patron of the arts.

This wasn’t strictly a case of class antagonism. The artists acquiesced when they allowed the rich capitalists into their club. The swallow tail jacket, according to the artists, was the uniform of wealth and waiters, and those that wore them were Philistines. The term swallow tail was to club members a synonym for pretension and artificiality, fakery, and “dull selfishness.” For posterity, they wrote in their annals, “For the life sap of this sturdy Bohemian, owl enshrining tree is good fellowship. True good fellowship cannot abide sham; humbug is fatal to it; hence ostentation, conceit, and all things that do not ring true, become the target for its pen and pencil.”

What the artists were seeing were fat cats who could not and did not add to the general entertainment, but sat themselves down in the choicest seats of the synagogue, and insolently shouted, “Now, amuse us!”

The club annals reported further:

Sharpshooters opened fire on the Swallow Tails with verse and picture; the heavy artillery of protest and invective thundered at it; the light cavalry of wit and satire charged down upon it; it was sapped and mined, and ridicule exploded beneath it. All of which must have eventually annihilated anything with a brain, but had little appears in effect on the Swallow Tail, except to increase its self-complacency by being made so important.

Pandemonium

It was decided by some of the rabble-rouser artists that, “the salt has been washed out of the Club by commercialism, that the chairs are too easy and the food too dainty, and that the true Bohemian spirit has departed.”

A parliament of painters and newspaper men were done with the “silk plush imitation Bohemian Clubs.” They seceded and formed a new club, which they christened the Pandemonium. They rented a room above a grocery store at Stockton and Morton streets and had a ceremonial shindig. Liberal rations of crackers, cheese, and beer were served and clay pipes were distributed. The night was brilliant with song and story and oratory, and was surcharged with wit and sarcasm, directed principally against the parent institution and its capitalist members.

After a few days the rebels began sidling back to the flesh pots of Pine Street. When rent came due at the end of the month, the Pandemonium gave up the ghost.

Some of the more established artists and journalists sided with the businessmen in their assessments of the grungier elements of the Club. Ambrose Bierce castigated the San Francisco Bohemian as “a lazy, loaferish, gluttonous, crapulent, dishonest duffer, who, according to the bent of his incapacity—the nature of the talents that heaven has liberally denied—scandalized society, disgraces literature, debauches art, and is an irreclaimable, inexpressible and incalculable nuisance.”

One time president Joseph Redding, who was an archetypal Renaissance Man … a writer, champion chess player, librettist, musician, lawyer and ichthyologist, acknowledged that there were “bum Bohemians” who acted sometimes like rapscallions, parasites, marauders, dead beats and “highbinders.”

Aspiring to wealth and respectability, Mark Twain tired of San Francisco’s Bohemian community years before the Club was founded. He saw the city as a “free, disorderly, grotesque society,” and denounced its Bohemian elements for their “dark histories, nervous breakdowns, and other behavioral extremes.”

From California. To the New York Island.

One ambitious club member who moved away from the city and the Bohemians seeking greener pastures around the time of the Swallow Tail/Pandemonium dust up was Henry George. He left for New York not long after self-publishing his manuscript Progress and Poverty: An Inquiry Into the Cause of Industrial Depressions, and of Increase of Want with Increase of Wealth. The Remedy. It was a book on economics, but instead of being dry and dull, it was clear, lively and compelling. And far reaching.

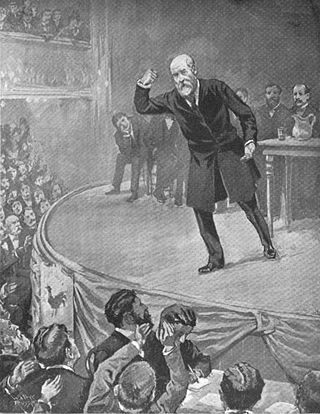

Progress and Poverty was George’s magnum opus and after accepting countless speaking engagements on lecture circuits, he became a populist firebrand known on two continents, and his book became a best seller. A few years after receiving a wide release, The San Francisco Examiner wrote, “the fact remains that no book of this century has made so profound a mark and initiated so universal a discussion.”

Many famous figures with diverse ideologies, such as George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, and Leo Tolstoy, mark their first encounters with Progress and Poverty as literally life-changing experiences. Clarence Darrow wrote that George had “found a new political gospel that bade fair to bring about the social equality and opportunity that has always been the dream of the idealist.”

Albert Einstein wrote, “Men like Henry George are rare unfortunately. One cannot imagine a more beautiful combination of intellectual keenness, artistic form and fervent love of justice. Every line is written as if for our generation.”

Other fans included Winston Churchill and Aldous Huxley. After reading selections of Progress and Poverty, Helen Keller found, “in Henry George’s philosophy a rare beauty and power of inspiration, and a splendid faith in the essential nobility of human nature.”

Father Edward McGlynn, who was temporarily excommunicated and defrocked for advocating for Henry George and his “radical views,” was quoted as saying, “That book is the work of a sage, of a seer, of a philosopher, of a poet. It is not merely political philosophy. It is a poem; it is a prophecy; it is a prayer.”

The Remedy

We cannot permit people to vote, then force them to beg. We cannot go on educating them, then refusing them the right to earn a living. We cannot go on chattering about inalienable human rights, then deny the inalienable right to the bounty of the Creator. – Henry George

George’s basic argument is that many of the problems that beset society, such as poverty, inequality, and economic booms and busts, could be attributed to the private ownership of a necessary resource, land. He recognized that the monopolistic control of land and natural resources (oil, gas, forests, water, minerals, etc) was the thing that stood in the way of eliminating poverty and all the social ills that it propagates. “The great cause of the inequality in the distribution of wealth, is inequality in the ownership of land,” according to George. Enormous concentration of wealth has always depended on the inherent right of the wealthy elite to seize and monopolize vast quantities of land and natural resources for personal profit.

In “Progress and Poverty,” George would completely deconstruct the current system of taxation and offer a totally new strategy. Wealth, according to George, is produced by a combination of three factors: land, capital and labor. Labor yields to workers their wages. Capital yields interest for investors. And landowners profit by collecting rent. Under the current system all means of acquiring wealth are taxed. George thought this was unfair especially to those who earned barely enough to have basic needs met. There is, however, enough wealth being gained through the control of natural resources to cover what would be provided by labor and capital, according to George. HG’s proposed solution to the land problem was the “Land Value Tax,” a tax on the annual rental value of land, which excludes the value of all improvements, such as buildings. He argued that government should be funded by a tax on land rent rather than taxes on labor. If land rents replaced taxes on labor as the main source of public revenue, socially created wealth would become available for use by the community, while the fruits of labor would remain private. He wrote:

To the extent that moving to cheaper land becomes difficult or impossible, workers will be reduced to a bare living no matter what they produce. Where land is monopolized they will live as virtual slaves. Despite enormous increase in productive power wages in the lower and wider layers of industry tend everywhere to the wages of slavery. Owning the land on which people must live is virtually the same as owning the people themselves. Poverty deepens as wealth increases. Wages fall while productivity grows all because land, the source of all wealth and the field of all labor, is monopolized. Unequal ownership of land causes unequal distribution of wealth. And because unequal ownership of land is inseparable from the recognition of individual property and land, it necessarily follows that there is only one remedy for the unjust distribution of wealth. We must make land common property.

George thought that income taxes and corporate taxes and even sales taxes and excise taxes can slow down the economy by discouraging production. HG argued that a single land tax would actually encourage and promote economic activity by discouraging people from hoarding land or just holding it for speculation. A land tax would encourage people and corporations who own tracts of vacant land, to either improve the land by building houses or farms or factories, etc. or selling it to somebody else who’s going to improve the land. Under George’s plan, land is used extremely efficiently and the land value tax generates revenue for the government to provide public goods and services. This single tax frees up wasted potential and provides more opportunities, while at the same time balances out wealth gained from land. Georgists of today advocate for the return of surplus public revenue to the people by means of a universal basic income or what Henry George referred to as a “citizen’s dividend.”

The Elections

All the talents of San Francisco were “in the throes of war” when the presidential election season hit the Bohemian Club in February of 1891. “There is strife among the illuminates and the trains and fashion of the town are disturbed to the verge of open rupture,” announced The Oakland Tribune.

There were, as usual, two tickets in the field, the “regular” ticket and the “opposition,” The outgoing directors who had been renominated campaigned on the fact that they had effected some radical changes during their term of office in the direction of improving and increasing the creature comforts which the club offered to its members. The club’s nominating committee submitted James D. Phelan, son of a rich liquor dealer for president and Edward Waterman “Ned” Townsend, the well-known author, for VP.

The Roseleaves caucus deliberated, and unanimously decided Dan O’Connell, the poet and journalist and one of the club’s few surviving charter members, to head the “Bohemian” or opposition ticket, with Stewart Menzies as his running mate. The Roseleaf Club included all the Bohemian and beer element of the club, and the “ham and eggs” or the “dudes” were the commercial faction–the tradesman and bankers of the club. The committee felt Mr. O’Connell was the incarnation of Bohemian fellowship and their loose and carefree ideas.

“The purpose of the Bohemian ticket has its origin in an endeavor to preserve the Bohemian Club from losing those early characteristics to which it owes its reputation, and with the hope that it shall not drift into an organization without any individuality,” wrote the Roseleaves. The only claim to distinction for the Bohemian Club was, after all, that its members were devotees of art and literature who aspired to higher things than the pursuit of wealth or position.

The Roseleaf Social and Boating Club, the inner penetralia of the Bohemia Club, was a band of bold buccaneers of the bay who leased the yacht Frolic from Commodore Harrison of Sausalito. The sub-club was the brain child of Dan O’Connell and painter Charles Rollo Peters. They were also the closest circle of friends of the Amy Crocker Gillig and her second husband Harry. The Roseleaves quickly earned the reputation of “harum-scarum, hard-drinking, irresponsible young blades,” who went on howling bay excursions and sang old sea-dogs songs. Members included not only Harry Gillig but past Bohemian club presidents Joseph D. Redding and “Uncle George” Bromley; Willis Polk, architect; George Nagle, famous humorist; “Prince of the Bohemians” Frank Unger, Harry’s best friend and “constant companion”; prolific playwright Clay Greene; Donald de V. Graham, the tenor; Edward Hamilton, political reporter from the Examiner; painters Emil Carlsen and Xavier Martinez; Williard T. Barton, author of Razzle-Dazzle; and Ned Townsend, author of the famous “Chimmie Fadden” series. That Townsend would run on the ham and eggs ticket was a disgrace to the Roseleaves (he later became a postmaster and a NJ Congressman).

These seafaring “laddybucks” also included a couple of Amy’s more intimate admirers and her ex, Porter Ashe.

Dan O’Connell had founded the Bohemian Club. He helped make it a roosting place to sing a song, tell a story, brew a punch, or engage in a game of pedro. He successfully attracted a circle of wit, whose company men sought out. Dan was a poet, litterateur, athlete, humorist, and a strong, deep, and extremely reflective thinker. He was an excellent boxer, a capital wrestler, a splendid swordsman, a great angler, and loved all kinds of outdoor life. “Had he not been a Celt, he would have been a gypsy,” according to friends.

Dan’s desire to spend, sadly, far exceeded his capacity to acquire.

Phelan perfectly represented the commercial element of club. His father was a liquor merchant who founded both the First National Gold Bank, (later as the First National Bank of San Francisco), and the Mutual Savings Bank of San Francisco. Phelan studied law at the University of California, Berkeley, and then followed his father into banking. The Oakland Tribune wrote article after article ridiculing Phelan, painting him as a spoiled rich kid and mamma’s boy “who never gets drunk and takes tea.” Jimmy had an “abbreviated body, dull eyes, and an accent that is an imitation of a New York valet’s imitation of his English brethren.” They noted:

He may be a prig, but he is not a loafer. He drinks lemonade, and never assaults the police, as becomes a man of five feet four, who has the shoulders of his coat stuffed for effect. He leads a clean, decent life, is neither a libertine nor a sneak, plays just a little, is given to posing, speaks well of no one nor ill or any one, is rather effeminate, and does not cause his father and mother much trouble.

The Tribune further surmised that he, “gets his ideas of life from novels written by women.”

Backers of Dan and the Roseleaves, the “O’Connellites,” were also known as the “green brigade,” and the “O’Phelanites,” were dubbed the “red division” because of their preference for St. George over St. Patrick.

“It was the last stand of Bohemia,” reported Ed Hamilton of The Examiner. Ed was the brains of the Roseleaf organization. The Regular Ticket from its entrenchment in the Board Room fired an array of statements and statistics calculated to create consternation in the enemy’s camp. The opposition feared that most of O’Connell’s supporters could not vote because they were behind in their dues. Phelan was rumored to have paid back dues of some of the indigent members. No less than $2300 of dues was paid by members during the day solely for the purposes of being able to record their votes.

Considerable excitement prevailed during the day and until the announcement of the result shortly after 12 o’clock. The result was a clean sweep for the regular ticket. Mr. Phelan had 232 votes to Mr. O’Connell’s 114. William Crocker was elected to the election committee. The Stockton Daily Mail predicted the landslide reporting that the Bohemian Club “was 90 per cent tallow and only 10 per cent Bohemian.”

The Roseleaves disbanded not long after they were sued by the man who leased the good ship Frolic to them for not settling their bill. This club morphed into another Bohemian Club offshoot, “The Owl’s Nest.” Dan O’Connell and Charles Rollo Peters were again founding members. The Roseleaf clan added William Randolph Hearst and Col. C.F. Crocker (the most Bohemian of the Crocker bros) to the Owl’s Nest roster. The plan was to lease three and a half acres for ten years, which in time would include the use of fifty additional acres adjoining the club site at a nominal sum. They secured the shooting privileges of 5,000 acres of upland. Architect Willis Polk designed a grand hunting and party lodge. A huge Bohemian owl, constructed by Marion Wells, the sculptor, would be placed at one end of the main hall.

A rift that wound up in court over who would pay the liquor and Ruinart bill after the rollicking cornerstone laying party led to the complete fizzling of their grand plan.

The only permanent schism in the Bohemian Club developed in 1902, when a group of members resigned to demonstrate their loyalty to William Randolph Hearst, whom the club had censured for his yellow journalism and for publishing a verse by Ambrose Bierce that seemed to advocate the assassination of President McKinley. Like earlier dissidents, the pro-Hearst faction, led by the political editor of the San Francisco Examiner, Roseleaf Ed Hamilton, insisted that they were trying merely to return Bohemia to its humble beginnings, its native simplicity, and its good fellowship. The reformed organization that they founded was named The Family, which later became almost as wealthy and sophisticated as the Bohemian Club. Amy’s ex husband Porter and her cousin Henry joined the troublemakers. Ed Hamilton became the president, known as “The Father.”

Harry and Amy Gillig Crocker, and perpetual sidekick Frank Unger, left California in 1891 to set up camp in Manhattan and on Long Island. Harry and Frank joined the Lambs Club, a Manhattan gentleman’s club for show folk, along with a few other Bohemian alumni including Clay Greene, who became the Lambs’ president or “Shepherd.” They formed their own Bohemian outpost on the East Coast. The Gilligs entertained their San Francisco comandantes often at the summer home in Larchmont, which they dubbed “La Hacienda,” and on their four yachts, the Gloriana, Glencarin II, the Vencedor, and the flagship 132-foot schooner Ramona.

Henry George, aka “The Prophet of San Francisco” ran for mayor of New York City in 1886. He received more votes than Republican Teddy Roosevelt, but was defeated by the Tammany Machine. He ran again in 1897 as a candidate of the Thomas Jefferson Democracy Party, at the peak of his popularity, against Democrat Robert A. Van Wyck. The acceptance of the nomination for Mayor interrupted HG in what he believed would be his most exhaustive and greatest work, The Science of Political Economy.

George vowed to enforce the law upon the rich and poor alike. He threatened to prosecute Tammany Hall tyrants Richard Croker and Senator Platt for various crimes like blackmailing city contractors. And he spoke constantly about the single tax. The strain of his grueling campaign schedule started to break him down. His speeches, delivered by the half-dozen a day, were often rambling and sometimes incoherent. His whole temperament underwent a complete change. Friends and family became alarmed.

The Bohemian Club’s greatest superstar and sage Henry George died in his bed just four days before the election of cerebral apoplexy. His body lay in state at Grand Central. Multitudes lined the streets for his funeral cortège; an estimated 100,000 mourners came to pay their respects. The New York Times wrote, “Not even Lincoln had a more glorious death.”

In the marketplace of economic ideas Henry George lost to both Karl Marx and the laissez-faire capitalists. Marx wrote of his rival, “George … has the repulsive presumption and arrogance which is displayed by all panacea-mongers without exception.” In America, the rags to riches stories of Herculean self-made men like Crocker, Huntington, Stanford and Hopkins, were too compelling. Individual rights and unrestrained markets was surely the key to a prosperous society, according to the masses, who still hold an unshakeable faith in “the American dream.” These stories, rare as they were, became proof, “of the justice of existing social conditions in rewarding prudence, foresight, industry, and thrift,” wrote Henry George, “whereas, the truth is that these fortunes are but the gains of monopoly, and are necessarily made at the expense of labor.”

“Progress and Poverty” had an impact around the world, in places such as Denmark, the United Kingdom, Australia, and New Zealand, where George’s influence was enormous. In 1906, a survey of British parliamentarians revealed that the American author’s writing was more popular than Walter Scott, John Stuart Mill, and William Shakespeare. Today P&P’s impact has fallen drastically, though it is far from an historical footnote. Singapore, Taiwan and Denmark use a version of land value tax. Interest in Henry George and his masterpiece are definitely on the rise as is talk of universal basic income. In California especially, where the rise of a billionaire class parallels an extreme homeless crisis never seen in the country before, people are taking a second look at their Prophet of San Francisco and the land value tax with much interest.

2700 Acres

In 1892, Harry Gillig, Amy Crocker’s second in command and second husband, bought some 50 acres of forest land west of Mill Valley at the foot of Tamalpais, known as Sequoia Canyon, through which meandered the crystal waters of Johnson’s Creek, with the idea of making it a permanent summer Jinks ground for the Bohemian Club. In early September they held a Buddha Jinks, Sermon of the Myriad Leaves. In the grove of big trees at the end of a gorge, Marion Wells, the sculptor, and his assistants labored for weeks rearing a huge image of Buddha modeled after the famous statue of Daibutsu of Kakamura. The Jinks was conceived and all the ceremonies arranged by Fred Somers, who had just returned from Japan a devout student of Sir Edwin Arnold, author of “The Light of Asia,” an epic poem about the life and teachings of the Buddha.

The Bohemians, however, found the forest too damp, and preferred their old rendezvous on Austin Creek and the Russian River.

In 1899, Club members finally found their permanent campground when they bought 160 acres from Melvin Cyrus Meeker in Monte Rio for $27,000. They found the land stunningly picturesque and wanted to save the trees from the steel teeth of a nearby timber mill. The Club in time expanded their private forest to 2,700 acres. It is a singularly glorious grove of thousand year old trees, some 300 feet in height. Bohemian Grove is among the largest privately owned campgrounds in the country, more than five times the size of Disneyland.

Amenities at the Grove include several amphitheaters and stages; a multi-purpose dining, drinking and entertainment clubhouse, designed by Bernard Maybeck, that is situated on a bluff overlooking the Russian River; an artificial lake; camp valets; and over a hundred separate posh camps scattered throughout the Grove. William H. Crocker, one of the Club’s most loved and celebrated Bohemians, was the captain of the “Land of Happiness” camp. Nobel Peace Prize winner Nicholas Murray Butler was one of his happy camper buddies. Templeton Crocker founded the “Zaca” camp, which famously hosted presidential candidate Robert Kennedy, who gave a rousing speech and received a standing ovation.

The now exceedingly rich and powerful Bohemian Club boasts a roster that has included U.S. presidents, many cabinet officials, CEOs of large corporations (including major financial institutions) and military contractors. Artists and lovers of art are still among the most active members, though the vast majority, since 1905, have been relegated to the category of associate members…

From the Redwood Forest to the Gulf Stream Waters

The Bohemian Club is a 501(c)(7) club “organized for pleasure, recreation, and other nonprofitable purposes” and granted exemption from federal taxes under the Revenue Act of 1916. They pay $250,000 a year in property taxes for their priceless reserve or around $93 an acre per year. Meanwhile the communities of Monte Rio and the nearby town of Guerneville, struggling with how to address homeless encampments that dot local streets and the bank of the Russian River, have finally approved a homeless services facility. Per capita the two small towns have four times as many homeless people as San Francisco. The tents that they currently live in are a little less posh than those used by their Bohemian neighbors.

Kevin Taylor is the official biographer for Aimee Crocker and a leading researcher on the Crocker Family. His many articles can be read at aimeecrocker.com

Be the first to comment on "2700 Acres: Henry George and the Bohemian Club"