By Kevin Taylor

Mrs. Amy Crocker Ashe Gillig – scandal-magnet and renegade daughter of Sacramento’s great philanthropic family – had gathered a circle of Buddhist devotees at her Manhattan “colony” who burned a lot of incense and midnight electricity. She would not attract a significant following, but a significant follower. Into her temple one day strolled Jackson Gouraud. Ragtime was in its popular infancy and Gouraud was a composer of current hits on Broadway. He was a romantic youth of 26 who soon became an Amy Crocker disciple. When he dedicated a ballad about roses and twilight to Amy, she couldn’t resist him. Mrs. Gillig hired him on to be her “private secretary.”

At box parties at the theaters, with Gouraud as the conspicuous chief cavalier at Mrs. Gillig’s side, they became the subject of comment among her friends and those of her husband. The favor shown to Gouraud by Mrs. Gillig was one of the main causes of a rift between husband and wife, according to some.

In no time, the millionheiress and young Jack, son of Thomas Edison’s agent Col. George Gouraud, considered themselves “affinities.” Amy enthused over Jack, and extended to him the gracious hospitality of the Oriental appointed apartments at her home. Before the ink dried on her divorce papers to Harry Gillig, Amy’s arm was inked with the initials of her young lover by Japanese tattoo artist Horitoyo Yoshisuke.

New York high society was aghast.

Jack had already attained moderate success as a musical author writing songs for some of the biggest shows at the grandest theaters, for the era’s most renowned stars. After setting the entire town singing with the broadly comic hit, “Waldorf-Hyphen-Astoria,” and after marrying the shining California glamour girl, The New-York Tribune wrote that Jackson’s career, “bordered on the sensational.”

The Gourauds, Amy and Jack, were the showiest of power couples along “the Great White Way.” Jack was given the designation of “The Best Dressed Man in New York.” He had 200 pairs of shoes and a tie for every day of the year. Columns were written about Amy’s appearance at theater openings during the pre-show fashion parade of gowns, jewels and coiffures. Soon her outstanding sartorial accoutrements made Mrs. Gouraud the central figure of this ante-play performance, which in many cases was more interesting than the regular one on the stage.

At the opening of Mile Mischief at the Lyric, Amy wore a sort of mottled flowered robe that might have come from the zenana of some Asian potentatess and was festooned with ropes of pearls like strings of popcorn on a Christmas tree. So striking was Amy’s black gauze flame gown that she wore at the opening of The Offenders at the Hudson Theatre, that “she divided attention with the play,” according to The New York World.

The Kansas City Star reported about another spectacular appearance:

At the opening of “Israel” … a whisper ran through the crowded lobby as her motor drove up to the door, and a way cleared for her as for a princess. Loitering dressmakers took out furtive lead pencils, but any sketching project they may have, fled from them when they beheld the costume that was revealed when she slipped out of the long ermine cloak that reached to her heels. It was literally a peacock gown. The bodice was of iridescence spangles in the peacock colors, and so was the front and upper part of the skirt. But the train–that was what made the sensation. Many a peacock has gone through life and died a proud death with less glory of tail than was displayed in the train that Mrs. Gouraud dragged down the aisle after her. From the tip end almost to the waist it was a perfect copy of a gorgeous peacock tail worked out in glittering spangles and beads. Around her neck was a high collar of emeralds and diamonds, a long diamond chain hung almost to her knees, and a hair ornament of diamonds and emeralds completed the effect. Naturally the audience didn’t care whether the curtain ever went up or not…

The First Nighters

In time the Gourauds became bona fide Broadway “first nighters.” A first nighter held a secured customary first or second row seat in the orchestra for all the big New York opening shows and only missed the first performance at any important theater when two plays opened on the same night. It was reported that once upon a time Jack Gouraud applied to a certain Broadway manager for a box at an opening performance. He replied, “What you ask is impossible. We insist that the show at to-night’s performance shall be on the stage, not in the boxes.” So the Gourauds occupied three or four seats in the orchestra circle forever afterwards.

The response of the first nighters or “death watch,” as they were called, carried more weight than the reviews of the critics to a play’s author, the acting troupe, and theater owners. It was against both custom and dignity for the habitues of the front rows to display enthusiasm. The authors trembled with suspense at the sight of the emotionless faces of the first nighters, while the players were driven to nervous prostration at the very thought of them. These theater magistrates included the Cornelius Vanderbilts, the J. Pierpont Morgans, the August Belmonts, the Chauncey M. Depews, the George Goulds, the Oliver H. P. Belmonts, Diamond Jim Brady and Lillian Russell, Charles Schwab, Mark Twain, the Stuyvesants, the Astors, the DeMilles, and Congressman and Mrs. Francis Burton Harrison (Amy’s cousins). The first nighters received more mentions oftentimes in the press than the actors, and none more than Amy and Jack.

The New and Improved 400

The Gourauds sashayed through New York during a period of transition in high society. Caroline Webster Schermerhorn Astor, aka Mrs. Astor, aka Lina (to a chosen few), ruled her 400 aristocrats in Gilded Age America like a crime boss. The exclusivity that the renowned arbiter elegantiarum created had unwavering oppressive rules. The upper classes were to be very Christian, very moral examples to all of civilization. Her appointed delegates were America’s version of royalty. By the end of the 1800s, the backbone of Mrs. Astor’s 400, as stiff and imposing as the ramrod of an old-time rifle, was beginning to limber up.

Gilded Age society entered into its second phase, a period of frivolity and excess that quickly overshadowed the last vestiges of nobility and restraint. Younger hostesses Mamie Stuyvesant Fish, Alva Vanderbilt Belmont and Tessie Oelrichs forming what was known as “The Triumvirate” were beginning to invite intriguing guests from the “Bohemian set” to their parties.

New York society plunged headlong into its last gasp of glory. The upper classes had grown tired of the dreary balls and dinners. Their parties became more lavish and entertainments more eccentric. The Triumvirate set out to buck the formality and rigidity that characterized social life in Gilded Age New York. The result was practical jokes and entertainments that brought disgrace onto the well-dressed, well-fed 400 and caused their rebuke in the nation’s pulpits and periodicals.

Mamie Fish was the most ludicrous of the trio. She gave the Baby Talk Dinner, at which guests spoke only in gibberish and the Heavenly Party, at which she hired messenger boys from Western Union to dress in skimpy shorts and parade among the guests as Cupids. At her Circus Ball, a live elephant wandered through the rooms of her house in New York so the guests could feed it peanuts. At the Dog’s Dinner, Mamie invited a hundred dogs, along with their masters, to a lavish feast. The canine guest of honor sported a new collar studded with $15,000 worth of diamonds, ranging from one sixth to one carat each.

Fish once gave a ball in honor of “Prince Del Drago of Corsica,” who turned out to be a well-dressed monkey. Amy Crocker outdid Miss Mamie’s practical joke when years later she gave a birthday dinner in honor of H.H. Kaa, Maharajah of Amber, who was not really an Indian potentate but a 12-foot boa constrictor. When he was introduced to the crowd, some of her guests screamed and ran for the exits.

Amy was a guest of honor at an after-hours country circus jamboree given by Harry Perry Disbecker featuring his pachydermic lady friend, Rosa, the elephant at the Hippodrome. He presented her formally to society with Mrs. Jackson Gouraud and actress Mme. Verona Jarbeau as her chaperones. Some 200 of the lively living set responded to invitations which Disbecker issued in the design of circus posters. Amy dressed as a genuine Westchester County dairy maid. At 12:30 the “grand parade” began. Disbecker came driving a trained pig. Jackson and assistant United States district attorney, D. Frank Lloyd, followed on horses dressed as policemen. After the parade, all the acts of the typical country circus were performed. Jackson, as the dastardly deputy, arrested three persons in the wee hours, one of them his wife, whom he charged with doing the “wiggle dance.”

New York society was clearly going to hell in a hand basket.

Such indecency left Caroline Astor adrift. The frantic search for frivolity and the increasing dominance of money as social power buried her concept of the Gilded Age, with its noble instincts and distinguished elite. She responded:

I hope my influence will be felt in one thing, and that is in discountenancing the undignified methods employed by certain New York women to attract a following. They have given entertainments that belonged under a circus tent rather than in a gentlewoman’s home. Their sole object is notoriety, a thing that no lady ever seeks, but, rather shrinks from. Women of this stamp are few in New York, but, alas! They are so appallingly alive!

The Old Guard looked at Mamie and Amy as destructive forces who encouraged the rise of hedonistic behavior that eventually brought scorn on all of Gilded Age society.

Mamie Fish was in every way Mrs. Astor’s antithesis. She hired Broadway stars to give private theatricals in her big white ballroom. In place of formal orchestras she engaged small bands to play lighter music. Fish hired early jazz bandleader and composer James Reese Europe’s all black band to entertain her crowd. She sprinkled her guest list with a handful of amusing, talented, attractive folks with no social claims including dancer Ruth St. Denis and comic actress Marie Dressler.

The high spirits and good conversation of actors made them ideal people to enliven a party. Indeed actors major contact with society outside the theater came as entertainers at dinner parties, where they were hired to work the crowd, to sing, tell stories, or give readings. It was always clear that they were hired workers, not invited guests. Usually they would remain downstairs until dinner finished, then be brought up to perform. The majority of Amy’s invited guests, in sharp contrast to the Triumvirate, were Broadway players. She didn’t just invite actors and playwrights and performers to her home, she ingratiated them. She helped bring them to the height of respectability. And eventually she became one of them. Ever so briefly…

Something’s Doing

In 1904, the Gourauds sent out invitations to all of the Bohemians and the stage folk and others of prominence in the white light district for a shindig at their Madison Avenue joint. The cards were simple but effectively inscribed, “Something’s Doing. Mr. and Mrs. Jackson Gouraud. Sunday, October 9th at 9 pm.” The press would call their party, “the highest priced vaudeville show of record.”

The audience included every one of importance in local stagedom. Edna Wallace Hopper, the first arrival, assisted the hostess in receiving. Actresses Edna May and her sister, Jane, were a center of interest throughout the evening. Lillian Russell was queenly; Cecilia Loftus was a serio-comic governess, who led in the funmaking. Headliners of the evening also included George Grossmith, Jr. and Virginia Earle. Jackson acted as the stage manager. The entire salon floor had been thrown open for the reception, and decorators had turned it into a bewitching scene, with a profusion of smilax and autumn leaves.

The vaudeville began at midnight. It was delightfully informal. The audience settled itself, and, not being provided with programs, began to arrange the performances by shouting demands for some impromptu entertainment. Lillian Russell was the first to be accosted by the boisterous crowd. Miss Russell obliged. Cecilia Loftus next fell victim to the merciless demand to be amused, and gave her famous imitations. Clarence Harvey contributed a monologue, and George Grossmith, Jr., introduced a new “specialty” or skit, which had not yet been tried on the general public. The frisky showfolk liked it tremendously. Virginia Earle sang; Dick Lee said saucy things about the guests; Edward S. Abeles gave his rendition of a popular specialty from the theatrical Lambs’ Club; and Emerson and Harry Foote played a banjo duet.

With everyone in the audience capable of lending a hand, the entertainment went on all night. Frank Unger, the trois in the Gillig’s ménage ten years earlier was there as was future son-in-law and stage manager Lewis Hooper. Soon to be superstar John Barrymore, at the time one of Jackson’s cronies, was also in attendance enjoying the hoopla. Van Bar’s orchestra furnished music throughout the reception, and Delmonico’s laid the spread, which was enjoyed while the vaudeville went on.

Amy’s lively salon gatherings and the Gouraud’s Sunday evening suppers were always well attended by a blitz of prominent literary and musical Bohemians. In reporting about the strange to-doings on Madison Avenue, The Morning Telegraph wrote, “Unlike Mrs. Gouraud’s first cousins, George Crocker and Mrs. Charles B. Alexander, the Gourauds care nothing for organized society.”

It was remarked that Amy was, “almost as familiar a figure on Broadway as the statue of Horace Greeley at Thirty-second St.” The Morning Telegraph announced the end of the theatrical season in April of 1904, after Mrs. and Mr. Jack Gouraud sailed for Bremen on the Kaiser Wilhelm II to summer in Germany. “There will, of course, be a few belated events of smaller interest, but no more real First Nights until next Fall,” reported the Telegraph, “No first night of the season past has been possible without them. None will be complete without them.”

Amy’s temerity and fortitude was on full display when, in an act of defiance, she threw her own raucous theater soirée inviting special guest American dwarf actor and humorist Marshall Wilder, the same night as Mrs. Astor’s Charity Ball at the Metropolitan Opera House.

The Divine Sarah Bernhardt

The West Coast, new money Crockers had been fraternizing and frolicking with showfolk for years. The Crocker men were popular Bohemian Club members who had the audacity to hold banquets for the likes of actor Henry Irving and playwright Oscar Wilde. They produced their own “hijinks” and “low jinks” plays with members playing all roles male and female. Amy’s first two husbands, Porter Ashe and Harry Gillig, were popular members. Both performed on the low jinks stages. Harry was known for his resonant baritone voice and the sleight of hand tricks that he performed at parties. He was also an early member of the resurrected Lambs Club, a men’s theatrical and dining club that extended back to early 19th century England.

n 1891, during the San Francisco leg of French actress Sarah Bernhardt’s tour, after performing on several stages, attending a prize fight and touring Chinatown, Sarah wound up her engagements, professional and otherwise, at a fashionable breakfast in her honor at the sacrosanct Nob Hill home of the young couple Will and Ethel Crocker.

The Crockers, plus two talented friends from the Bohemian Club, George Hall and Northrope Cowles, treated the “Divine Sarah” like a visiting dignitary. La France and niphetos roses were amassed throughout the mansion. The breakfast was not elaborate, they served strawberries, terrapin, and a petit filet, but it was delicious. The party adjourned to the exquisite Louis Quinze room where Madame Bernhardt went into the raptures over the tapestries prepared from the studies of Jean Honore Fragonard. Bohemian George Hall sang songs.

Ethel Crocker, 1894, from the Charles and Gretchen de Limur collection

Reporters were outraged and criticized the Crockers, saying entertaining Bernhardt imperiled the good name of their glorious city. The Argonaut deduced, “If the incident which introduced this unspeakable woman to one of the most elegant and exclusive of Nob Hill mansions may not be regarded as a social blunder, arising from youthful indiscretion and ignorance of the world, it must be viewed as a crime against all the rules of social civilization.”

Actresses had always been accepted by male society, by and large, though their role within it was tightly prescribed. But the willingness of a high-born woman to fraternize with an actress was unfathomable and unforgivable. Even in liberal and progressive San Francisco. Ethel was skewered.

Sarah Bernhardt was the most celebrated actress in the world throughout the Gilded Age/Belle Époque. Mark Twain once said there are “bad actresses, fair actresses, good actresses, great actresses – and then there is Sarah.” Yet Bernhardt’s flaunting of conventional morality offstage and her racy performances in the theater led to a storm of protest in the press and from the pulpit wherever she performed. Ministers denounced the perverted Parisienne and exhorted their charges to stay away from her performances.

When American actress Lillian Russell visited Chicago’s Washington Park racetrack on Derby Day in 1893 and ventured into the clubhouse, the haunt of Chicago society, her presence so upset the city’s aristocrats that the president of the racing association asked her to go to the grandstand.

For a large swath of society, the differences between the actress’s life and the prostitute’s or “demimondaine’s” were indistinguishable. Presbyterian clergyman Herrick Johnson questioned, “How can they mingle together as they do and make public exhibitions of themselves as they do, in such positions as they must sometimes take, affecting such sentiments and passions—how can they do this without moral contamination?”

Reverend Perry Sinks voiced similar concerns about actor’s work: “The life of an actor is a fictitious one, being made up of the personation of other characters, often gross and immoral, even diabolical. It is a subtle law which governs in all histrionic art that one must have sympathy for the role he plays or the character he paints in his acting hence the danger of personating evil characters.”

Though Shakespeare was considered half-divine, his interpreters were considered more than half wicked and depraved.

The vast majority of performers at the turn of the 20th century belonged to traveling troupes. Touring combinations burgeoned, peaking in December of 1904, when 420 companies were touring. Except for the leading figures of the stage, who commanded a certain respect and admiration, troupe actors lived as gypsies, as carnies, in squalor and incessant self-denigration. High society often maligned them. The public’s regard for its performers at the fin de siècle was mixed and ran to extremes, from unbounded affection to unbridled scorn.

In 1895 Queen Victoria knighted actor Henry Irving which bestowed a new eminence on the player’s profession and opened the way for other actors to be similarly honored in the following years. Supporters of the American theater hoped that Irving’s celebrated knighthood would signal a new day for their actors as well.

Times they were a changin. At least in the legitimate theater. Ethel Barrymore attained praise on the London stage, and then scored an even greater success in English society after becoming the only actress invited to Queen Victoria’s 1897 Jubilee Ball and after being wooed by a bevy of suiters including Sir Winston Churchill. Upper class men increasingly came to regard the stage as a viable marriage market in which to shop. New York papers covered Barrymore’s triumph in full, and on returning to America she found herself welcomed into the finest homes of Boston, New York, and Philadelphia. As the nineteenth century gave way to the twentieth both clergyman and socialite found their social leadership undermined by forces beyond their control. They witnessed the sudden prestige of a group long assumed to be subordinate to them.

The defeated Mrs. Astor responded by hiring tastemaker, artist extraordinaire and lifestyle coach Edmund Russell and his dress reformer wife Henrietta to teach her some “Delsartean” techniques designed for actors to express themselves more soulfully and creatively. Astor dumped the pompous Ward McCallister as her major domo finding a replacement in Harry Lehr, Newport and New York society’s class clown, who in no time became her chamberlain, advisor, and court jester. Whereas Caroline Astor was dignified, reserved and proper, Harry was all impulses and unbridled extravagance. Flamboyant and at times coarse, it was impossible for anyone to be bored in his company. It became impossible to have a party without him. Lehr and the Russells helped the ageing dowager, the Queen of the Gilded Age, to lighten up ever so slightly.

Striving to upstage her young rivals, Lina Astor did sponsor and promote the eccentric and Bohemian modern dancer Isadora Duncan in 1898 when she gave open air dance recitals for society women in New York, Massachusetts and Newport, Rhode Island. Isadora danced while her sister Elizabeth read passages from A Midsummer Night’s Dream to music by German composer Mendelssohn, and An Idyll from Theocritus, to music by pianist Ethelbert Nevin. Isadora also danced to quatrains from the Sufi cult classic The Rubáiyát of Omar Khayyám. Guests looked on with puzzlement. Backing Duncan was a decidedly hipster move for the fin de siècle matriarch.

Black Listed

The new and improved and more progressive 400 would chit chat with the dazzling Gourauds at the theater, but never would they invite the power couple to their homes. If Amy was a nouveau riche interloper, Jack, though pretty and well dressed, was a song and dance man, an entertainer, an “upper servant” at best. What’s worse, he participated not in legitimate theater but in the lowest of low brow entertainments–ragtime, burlesque, cabaret, coon songs, minstrel shows, vaudeville…and other bawdy entertainments where risqué jokes and indecent behavior were applauded. Going to some theaters at that time was the equivalent to going slumming. Only the most daring wealthy patrons would attend.

Amy, with her tattoos and her piano man ten-years her junior, crossed class boundaries and age brackets and convoluted gender roles to a degree that brought out vestiges of obstinate Victorianism within the Triumvirate. As liberal and fun loving as they were, the new Gilded Age leaders believed strongly in class demarcation. They enjoyed the capering comedians, they wept at renditions of sentimental ballads and they loved discussing fashion and the culinary arts with stage stars. But let the performers overstay their welcome a few moments or otherwise trespass the invisible boundary between themselves and their hosts, and very visible signs of denunciation appeared. One could intermingle with the lower classes, but not commingle with them.

The bold and unrepentant Crocker ruled over her own clique, her own class in Manhattan society, the Swagger set, which was a perfect polygamous marriage between the risqué new rich, the successful Broadwayites and the mystic Bohemians of New York. The truth seekers and the thrill seekers. The press would name her “The Queen of Bohemia.”

On Thursday evening, February 17, 1910, Jackson Gouraud, first nighter, songwriter, fashion plate and man-about-town, died at his Manhattan home from an acute attack of tonsillitis followed by blood poisoning. The illness took him in less than a week. “Even at the last it was said that his death was unexpected,” reported The New York Times. He was 35 years old. Grief stricken, Amy went abroad with her brother-in-law, Bayard.

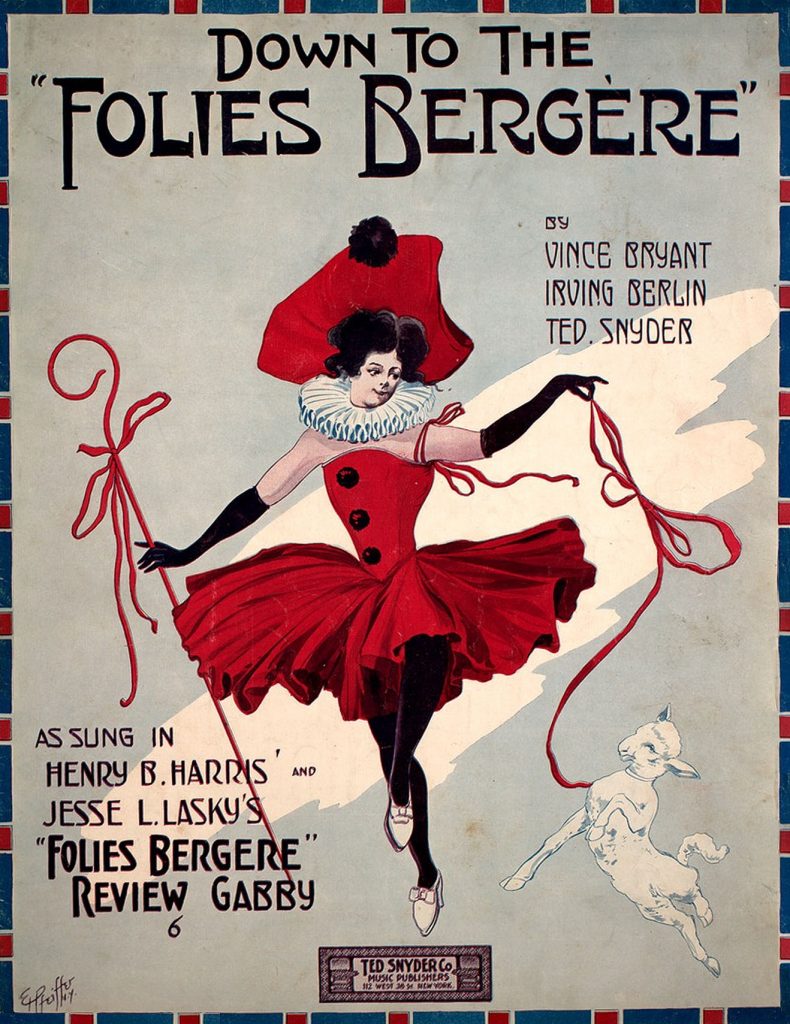

Folies Bergère

The event of the season in the spring of 1911 was the grand opening of the new Folies Bergère at 46th and Broadway, a first-class restaurant attached to a theater and the most original amusement temple in the theater district. It was situated within kissing distance of two well-known Broadway theaters: the Globe and the Gaiety. The new theater was heralded as “more Parisian than Paris” a reproduction of a Continental music hall. All of Manhattan was abuzz during construction, especially Francophile Amy Crocker Ashe Gillig Gouraud.

The two promoters, H.B. Harris and Jesse Lasky, introduced a champagne bar, a cigar stand, a balcony promenade, and the first midnight performance in New York. The combination of music & spectacle and food & drink was unheard-of in New York at the time.

The house had the interior of a jewel box with a scheme of pearl pink and French “elephant’s breath” gray. The table tops had pink silk inlaid, covered with Cluny lace and protected by French beveled glass. Each was illuminated with pink shaded candelabras. Red glowing buttons alerted waiters that some delicacy was to be ordered from the long menu.

They hoped that Folies Bergère would be a rallying place for the reckless rich to fling their money.

A “coup de publicity” was leaked before the grand opening of the grand theater. A character representing fabulous first nighter Aimée Crocker would be in one of the numbers.

An emissary from the Folies Bergère asked Aimée (she changed the spelling of her first name in 1910) if their costumer could copy her Callot Soeurs sequin gown, which had created a sensation at a recent first night. Mrs. Gouraud pondered. She finally announced to the theatrical envoy that if she was to be represented on the stage, she wanted it done well, and so she would have to play the part herself. The theatrical man gasped for joy, and half an hour later the celebrated Californian was duly signed up as one of the cast to perform a small scene stealing cameo. She was well-acquainted with most of the prominent actors and would have the opportunity of seeing how first nighters look to the players from on stage.

Aimée, though wracked with stage fright, relished the challenge, saying:

I came to the rehearsal on one impulse and I remained on another. Above all things, I hate to be an onlooker in life. That has been the fly in the ointment of being a confirmed first-nighter. I have always envied the men and women who were putting the play across. And I do love to do the thing that every one thinks I cannot do. That is why I lived the lives of natives when traveling in foreign countries. I was not satisfied with seeing what the average tourist sees. That is why I seek companionship among the artists of Paris, though I cannot paint. That is why I wrote my book Moon Madness…It has been said that my histrionic ability is represented by two “best seats” for every opening performance. Well we will see. But I think that what finally determined me this time was the atmosphere in which the play will be produced. I love Paris. The Folies Bergère promises to be a bit of Paris transported to Broadway…it promises to be the very environment I like and I mean to enjoy it. That’s about all we get out of life, rich or poor, isn’t it, a few hours of enjoyment here and there? I think it is folly to allow a single chance for pleasure to slip past you…

The Morning Telegraph reported that “in the history of New York theatre-going, there perhaps has never been an event that equalled the opening of the new Folies Bergère, [which] is at once a café, a music hall, a theatre, a restaurant, a club.” Admission tickets for opening night were sold at auction one week earlier, bringing in $14,242, a phenomenal sum at that time.

All Aimée had to do was speak a few lines, but she rehearsed her part diligently. Two full weeks before opening night the entire organization, including phalanxes of chorus girls, comedians, a large orchestra, various managers, relatives, friends and chauffeurs went off to Atlantic City for a trial run at the Apollo Theater.

On April 27, 1911, at 6 pm, the Folies Bergère opened its doors. As the patrons perused the menu and nibbled appetizers, mandolin and guitar players, violinists, singers and dancers from Madrid, Vienna and Budapest warmed up the crowd. At 8:15, the curtain rose on the first of a triple bill — a “profane burlesque” (or travesty) called Hell, which would be followed by a one act ballet Temptations with forty dancers choreographed by Alfredo Curti of Paris; and then a “satirical revuette” Gaby, based on the much publicized love affair between Aimée’s friend, French actress Gaby Deslys and King Manuel of Portugal.

Aimée appeared in the opening burlesque Hell, written by Rennold Wolf, with music by Robert Hood Bowers, Maurice Levi and future legend Irving Berlin. Berlin quickly came up with a replacement number for an obvious weak link “The Messenger Boy” in Hell. It was “Alexander’s Ragtime Band” which didn’t make it to the New York opening, but showed up months later as a prominent part of the new evening-ending cabaret show entitled Hello Paris. And elsewhere.

The author called it a “profane satire.” Wolf’s version of hell was a place of pleasure. Hades is depicted as “the most popular of winter resorts.” Electric fans and cold beverages mitigated the heat. No torture in this eternal damnation; it was no more devilish than a hangover after a night of too much champagne. Otis Harlan played a jovial Beelzebub and Ada Lewis was his virago wife. In the story, the Devil, who performs Will Rogers lariat tricks with his tail, boots various New Yorkers out of hell for being altogether too sinful for it. “All the good people go to heaven,” declares the Devil; “all the best people come here.”

Enter Mrs. Jackson Gouraud, or in the production, Mrs. Maxom Newrow. Aimée appears watching an opening night performance of an opera accompanied by a Pittsburgh magnate, played by Theodore Marston. They exchange barbs about celebrated Italian tenor, Signor Robingem (Enrico) Caruso. Aimée is not impressed. Recreating her familiar languid saunter and bored ennui that characterized her in an audience, she yawns and declares, “This is all very ordinary. Can’t we have a monkey dinner or a reptile tea?” She fans herself lazily and loafs out of sight.

Her role was soon handed back to actress Mayme Kelso.

The evening received a positive review from The New York Times, praising the spectacle and variety, and marveling at the combination of performance and food in one locale.

Life Magazine called it a shallow but well-presented light comedy. A reviewer from Munsey’s Magazine wrote that Rennold Wolf’s Hell was the best feature of the triple bill, although, “may be caviar to the stranger within our gates.”

Although critics were impressed, the theater’s premiere was not perfect. Between the acts of Hell a standpipe in the elevator shaft burst, releasing five thousand gallons of water which came crashing through the ceiling over the theater’s east entrance drenching the lobby and many in the audience. They went home happy, a little soggy, and considerably poorer, for it was estimated the evening cost each couple over $35 (more than $1,000 today). Despite glowing reviews Folies Bergère proved to be simply too expensive in an era of fifty-cent theater tickets and dollar meals. After three months the house closed for major remodeling and then reopened as the Fulton. It became just another Broadway playhouse.

The following year, Yankee Doodle Dandy and Broadway legend George M. Cohan gave high regards to Aimée Crocker by modelling a character after the popular heiress in his play Broadway Jones. In it Jackson “Broadway” Jones, a bored small-town chewing gum factory scion, moves to New York where he goes broke living it up. He almost marries a rich widow, Mrs. Ambrose Gerard (played by Ada Gilman) to fund his new lifestyle, but he inherits the factory and decides to return home to his sweetheart. The El Paso Herald wrote: “Broadway Jones is a surprise in many ways. Who would have thought that George M. Cohan could cut out both his singing and dancing, and still make a hit. Well, not a song is torn off, not a dance stepped, nor even a flag waved, and the show is the biggest laughing hit of the season so far.”

This stage play formed the basis for the stellar author/actor’s silent screen debut a few years later. Mrs. Gerard was played by Ida Darling in the film. Critics raved. The New York Journal wrote, “George Cohan, in Broadway Jones, is the greatest comedy feature ever produced, and will take first prize in every theater in America. This picture has stamped George Cohan the greatest artist in the world.” The story returned a third time in 1928 as the musical Billie. It would the last musical that George M. Cohan ever wrote.

Broadway would commemorate its favorite flamboyant heiress a third time in 1917 with the modern society comedy The Lassoo, by Victor Mapes, which opened at the Lyceum Theater in New York to much less fanfare. There was included some poignant marital advice passed along from the lips of the Aimée character (played by Helen Westley) that no doubt caused some chuckles, “What we’re after is a good time, as much pleasure and excitement as we can get and if the right man comes along and falls in love with me, why the devil should I turn him down?” Though the play received mixed reviews, Miss Westley’s impersonation was praised across the board.

Three Queens

In the opinion of Sarah Bernhardt, queens, prima donnas and great actresses were not to be bound by the rules of conduct necessary to keep ordinary mortals in order. Her appearance at the Nob Hill mansion of Ethel and Will Crocker back in 1891 turned the tides and helped reposition and elevate the role of actresses in society. Several newspapers defended Ethel’s actions. The Los Angeles Herald wrote:

No doubt the genius of the divine Sarah was at its perihelion, and that the coruscations of wit rivaled in brilliancy the sparkle of the wine. That being the case, everybody ought to be satisfied, Mrs. Crocker because she has succeeded in getting herself more talked about than any woman in San Francisco, the Bernhardt, because she has had a delicious repast served by a charming hostess, the Mrs. Grundies because they have had an opportunity to scold and find fault, and the general public because they have had a hearty laugh at the absurdity of it all. It is quite apparent that Mrs. Will Crocker knows a thing or two about attaining fame at a bound, and her cool audacity marks her out for a social leader of the first eminence.

The Oakland Tribune wrote a simple and poignant solution to the conundrum of how to respond to artists with tainted pasts: “People weren’t going to deny themselves the pleasures of art on account of the character of the artists.” Bernhardt was the Queen of the Theater in spite of any detractors.

In 1912, the Rev. Dr. Charles Wilbur de Lyon Nicholls, once dubbed “Ward McAllister’s first Apostle on the Philosophy of Society” crowned Ethel Crocker as the “Leader of the Ultra Fashionables” on the West Coast. She became San Francisco’s version of Mrs. Astor. But without the iron fist.

While Ethel Crocker opened the door for actresses to gain acceptance in society, cousin Aimée opened the floodgates. After Jackson died and after Aimée’s stunt on Broadway, the unruly heiress was linked romantically to several showmen–Russian opera singer Genia D’Agarioff, musician and fashion designer Melville Ellis, Argentinian composer Eduardo Garcia-Mansilla, and Édouard de Max, the Divine Sarah Bernhardt’s leading man in 20 productions.

Tongues wagged when Aimée got private dance lessons upstairs at Maxim’s from teenager Rudolph Valentino. She referred to him as her protégé.

Aimée Crocker’s life became performance art or a reality show serial drama that rivaled the most fantastic spectacles seen on the stage or the screen. The public followed her antics with glee and her heartaches with sorrow throughout her entire adult life. High society would always keep Aimée Crocker, the Queen of Bohemia, at bay. Family members shunned her. She would, however, remain a friend, supporter and a champion to Broadway. The press would, at the end of her career in the limelight, declare her “the Most Fantastic Woman of Her Age.”

Kevin Taylor is the official biographer for Aimee Crocker and a leading researcher on the Crocker Family. His many articles can be read at aimeecrocker.com

Be the first to comment on "The Crocker chronicles: Actresses will happen even in the best of families"