Sacramento writer sees attention, promising sales around his unlikely pitch for a maligned musical genre

By Casey Rafter

Joyful horns, bass and guitars flowed from speakers and echoed by murals paying tribute to musical art through images of vinyl records, bouncing notes and colorful graffiti tags. As a small crowd gathered in the sunshine outside Phono Select Records, journalist and author Aaron Carnes was ready to make his case for those blasting sounds – and ready to explain why he’d penned his new book “In Defense of Ska.”

The audience was ready, too. Heads and feet moved to the sound of “Gangsters” by The Specials, and the wakka-wakka of Lynval Golding’s rhythm guitar colored the air. After greeting the crowd and signing copies of his book, Carnes was introduced by comedian and fellow ska fan, Keith Lowell Jensen.

“We’ve been listening to Aaron Carnes’ ‘In Defense of Ska’ playlist on Spotify; that was my idea,” Jensen laughed. “[If] we’re going to start giving me credit for things, he was originally going to write a book called ‘In Defense of Capitalism,’ but I said, ‘Maybe ska? You like ska, too. That would be better,’ so you’re welcome.”

The title serves the book well, but the pages within “In Defense of Ska” contain more than a plea for readers to stop dismissing the genre — known for its fast, offbeat tempo and use of horns on top of traditional rock or punk instruments — or snickering at their ska-loving friends. Throughout the book, Carnes provides anecdotes that read like a recording of his many music-based religious experiences.

In one anecdote, Carnes recalled attending a ska show featuring Columbian ska band Memoria Insufiente. During the show, he realized that ska has the ability to cut through all cultures.

“They’re covering ‘2-Tone Army’ by The Toasters, but in Spanish. In this moment, I realized how complex culture is and how it’s all captured in the style of the music that I love,” Carnes said, reading from his book. “[The] song is written by a New York band, referencing a British record label that revived Jamaican music. It’s being played by a Columbian band and enjoyed by Mexican teenagers.”

Carnes, who became a music journalist in 2009, understood that ska wasn’t taken seriously, most notably by his journalist peers. Popular books about music have rarely validated ska as a part of the zeitgeist of American music in the 1980s and ’90s. He explained that “In Defense of Ska” is his effort to beat naysayers to the punch and halt the reflexive scoff at the mention of the word “ska.”

“It’s like ska bands were removed from that conversation,” Carnes explained. “The more I was working as a journalist, the more clear it became to me that it was just a punchline. They didn’t really have their own version of it. I thought about defending ska as a fun way to comment on ska’s place in culture. [To say,] ‘I read a book about how you think ska sucks, but you’re wrong.'”

Jensen discussed Carnes’ rejection of the idea that ska has progressed through “waves” as different cultures learned of the styles specific to that genre. Carnes acknowledges that ska originated in Jamaica — pre-empting reggae — then spread to Great Britain before migrating to the United States in the 1980s, but he submits that it maintained a consistent presence in the zeitgeist throughout these eras. In his book, Carnes speculated about where ska may spread next.

“In that Mexico chapter, I did say that if we were to buy into the wave argument, Mexico would be the fourth wave,” Carnes said. “Most of those [Mexican] bands heard of ska from American bands in the ’90s. The wave theory of Ska says that it comes and goes — I don’t see it that way. I see that ska came from Jamaica [and] evolved into reggae. Two-tone bands [in Britain] revived ska. It’s been a reference point — with the exception of the bands that are specifically going for an old Jamaican sound. Two-tone was so popular in England, and it became such a cult thing in the U.S. that it really sent ripples all over the world.”

Carnes added that most ska that migrated to the United States is a version of the British revival. Bands playing 2-tone and ska in the United States began doing so in 1980 and 1981. Though the genre was established in the U.S., it didn’t gain notoriety until the mid-1990s. By then, ska culture had roots firmly established in many metropolitan cities.

“The [bands playing ska in the U.S.] were all extremely popular in their perspective scenes,” he noted. “Then they started touring, you’d see record labels forming, you’d see zines forming. When ska became popular in the ’90s, it [had] spent 15 years as a consistent genre in the U.S.. So to think of it as a wave is kind of a silly way to think of it. When the music became unpopular, the music continued to exist.”

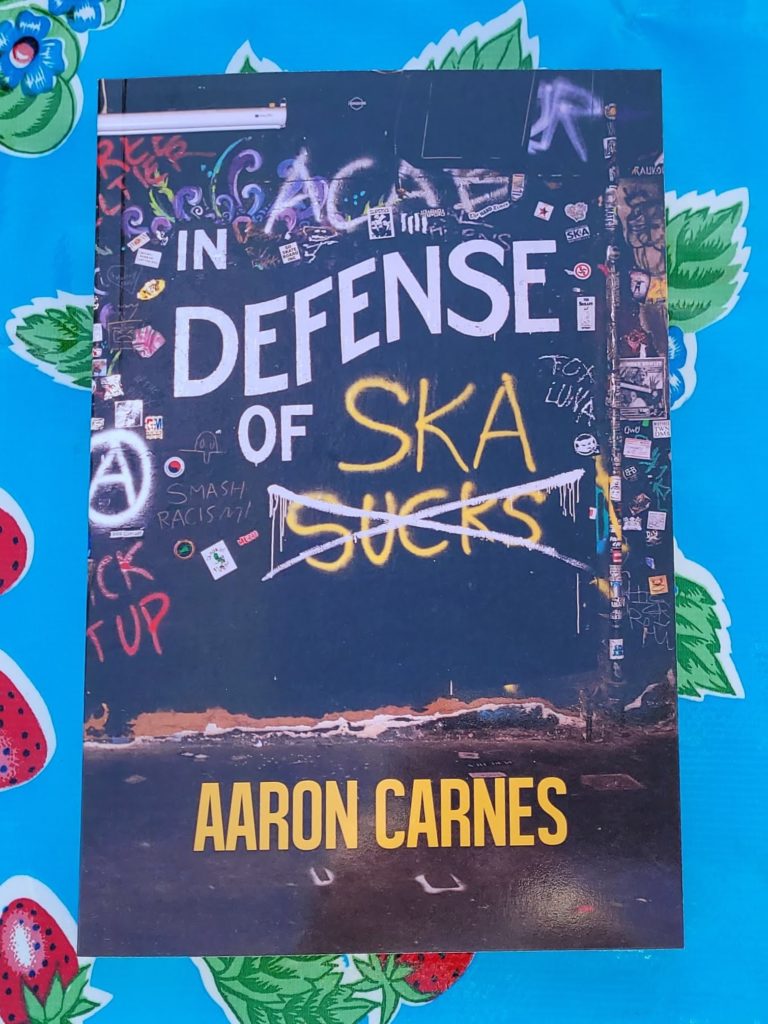

The cover of Carnes’ book was photographed by Cam Evans, who Carnes interviewed in 2018 about the 60-page photography magazine Evans created, “Sacramento is Burning!” In July 2020, Carnes, Evans and lettering artist Ken Davis spent eight masked, hot, mid-pandemic hours at 924 Gilman, an all-ages music venue in Berkeley.

“I’ve been following the guy, and we’ve been keeping in contact ever since,” Evans said. “That’s how I got the opportunity to go with him to Gilman to photograph the cover of ‘In Defense of Ska.’”

Carnes initially pitched the idea depicted on the cover to his publishers. In response, they had a cartoonist provide an interpretation, but Carnes was given one opportunity to create a scene to photograph for his book. He said on the day of the shoot, he was wrought with anxiety.

“I was stressed the whole time — this was my one shot to convince my publishers that we could do a photo version of this book cover,” Carnes recalled. “Some of the graffitti [on the cover] is just the Gilman graffitti and some we added. On the back, the only thing we did was add a trombone on the merch table

Jensen praised Carnes for using something DIY, much like the bands that perform the music Carnes writes about.

“This isn’t a picture of a wall with the lettering then Photoshopped onto it: This is actually hand painted on an actual wall at the Gilman Street Project,” Jensen said. “I’m glad they rejected the drawing [Carnes] first proposed.”

Evans confesses that, though he has a lot of love for ska, Carnes’ book has given him fresh insight as well as some familiar comfort.

“I’ve been reading the book recently. It’s like a warm blanket to me,” Evans acknowledged. “I am a huge fan of ska. It was the genre that got me into punk rock. Some details I knew about and some things were totally new to me.”

Often, music fanatics can refer to a point of origin for their favorite artist, album or genre. Carnes discovered ska in the early 1990s before many so-called “third wave” American bands gained the attention of the youth of that time. He said that most people from his generation found ska during a live performance.

“I was just a kid from Gilroy – I loved alternative music, but I felt really intimidated at those shows,” Carnes said. “I was really into Primus and went to Primus shows but the audience scared me. I don’t know why, Primus is very nerdy.”

“I saw Skankin’ Pickle in 1992. They used to wear costumes and have props,” Carnes went on. “That blew my mind. I loved that the audience felt extremely welcoming and inviting to me. The shows were wacky and pretty silly, but then they’d have songs about how they hate racism and they’d just sing a serious song about that. They were serious about stuff I really cared about.”

Carnes does a great service to ska and its culture in the pages of “In Defense of Ska,” providing fans, haters and the uninitiated ska’s history and drawing a path for its possible future. In his book, he speaks both about the feeling of belonging to this unique and welcoming subculture of society, but also a sense of ownership over the thing that drives his passion.

“We love ska wholly. We didn’t care who made fun of us. We laughed at them for missing out on the pure joy of this music.”

Nice article, Mr. Rafter, triggered my curiosity to learn more about this music