When it comes to ‘preventing violent extremism,’ critics worry Muslims are the focus—even in California.

A Sacramento nonprofit that serves refugees and immigrants has been tugged into a debate swirling within American Muslim communities about whether a federally funded program aimed at intercepting “violent extremism” is intended to serve them—or spy on them.

In October, Opening Doors was awarded one of five grants from the U.S. Department of Homeland Security and funneled through the California Office of Emergency Services “to prevent potential homegrown and domestic violent extremism impacting our communities,” CalOES Director Mark Ghilarducci said in a release.

Critics of the program describe it as insidiously designed—paying Islamic community organizations to collect data on their clients and allow law enforcement into their spaces.

“When you have government or state money involved in ‘countering violent extremism,’ it is inextricably linked to the law enforcement framework,” said Hammad A. Alam, a staff attorney with Asian Americans Advancing Justice in Los Angeles. “This money comes with requirements or strings in some way, particularly for groups that work with vulnerable populations.”

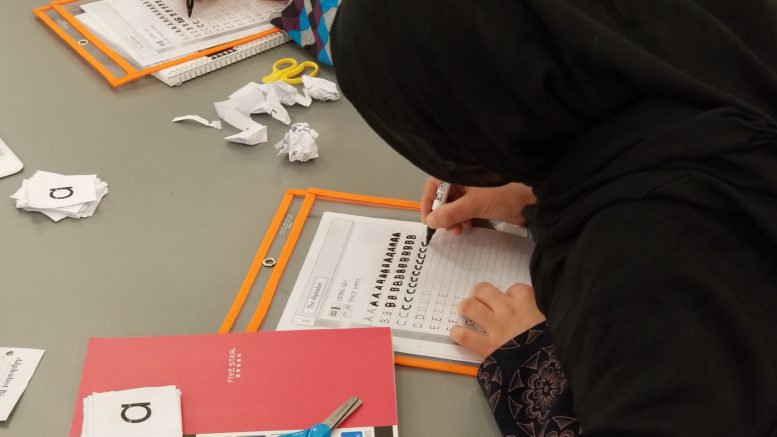

Representatives at Opening Doors say the money is supporting groundbreaking trauma-intervention and literacy services that otherwise wouldn’t exist.

“I think if you left off the ‘extremism’ part and say are we combating violence, I think that’s more appropriate, because we’re preventing domestic violence,” said Jasmine Ali, Opening Doors’ family trauma intervention coordinator. “It’s not extremism because we’re not talking about radicalization, we’re not talking about any of those things.”

Ali said she “grilled” CalOES officials in a meeting prior to applying for the grant about what the agency wanted in return, and determined Opening Doors would only be required to provide basic numbers about how many clients are being served by its expanded counseling services.

“Nothing that we’re doing can lead to any type of surveillance issues or any type of stigmatizing for our clients, because their names, their initials, [that] information is never released,” she said. “And the only way that we’re addressing that violence part of that question is really within the home.”

Even with a California agency as the intermediary, some civil rights groups remain skeptical than any good can come of a financial partnership between the Trump administration and nonprofits reliant on government contracts to survive.

This debate actually started flickering during President Barack Obama’s first term, when his administration developed the Countering Violent Extremism program in 2011.

Congress freed up $10 million for the Department of Homeland Security to put CVE into play in 2016, prompting civil rights groups to flash on the resulting nonprofit partnerships as “de facto surveillance gathering programs under the guise of ‘community outreach,’” the Council on American-Islamic Relations, California and Asian Americans Advancing Justice wrote in a joint statement announcing their request for government records.

The lack of trust in the federal government as an unbiased monitor of violent extremism dates back to at least 1956, when the FBI started a secret counterintelligence program targeting domestic Communists. Known as COINTELPRO, the program was expanded to infiltrate, discredit and sabotage the Black Panther Party, Native American groups and civil rights leaders such as Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X.

The FBI even admits the program went too far in a short, qualified mea culpa on its website, stating that COINTELPRO ops, which it says ended in 1971, was “later rightfully criticized by Congress and the American people for abridging first amendment rights and for other reasons.”

Critics of CVE say it is similarly prone to abuse and bias. The Brennan Center for Justice released an analysis in June showing that 85 percent of CVE grants awarded during the Trump administration targeted Muslim and other minority communities.

“It’s expanding,” said Sophia DenUyl, a researcher with Brennan Center’s Liberty and National Security Program.

Meanwhile, Mother Jones’ database on mass shootings shows the money is missing the most dangerous demographic.

Since 2016, there have been 32 mass shootings in America, resulting in the deaths of 281 people and injuries to 747 others. Half of the shooters have been white and they have been responsible for more than half of the fatalities.

The only shooter in the past three years with possible Islamic extremist ties was Omar Mateen, who killed 49 and injured 53 at the Pulse nightclub in Orlando, Fla. in June 2016.

CVE got a soft rebranding when it came to California last year as the Preventing Violent Extremism Nonprofit Pilot Grant Program, known as PVE.

Asian Americans Advancing Justice-Los Angeles and CAIR of Greater Los Angeles raised red flags about PVE when CalOES started soliciting grant applicants last fall. The groups say government documents they’ve obtained through a public records lawsuit show that California’s violent extremism program remains disproportionately interested in Muslim and minority communities, rather than the lone white wolves responsible for some of the more recent acts of terrorist depravity, including indiscriminate shootings in New Zealand mosques, a Thousand Oaks nightclub and a synagogue in Pittsburgh.

“That’s been revealed through thousands of documents, at least,” Alam said.

“CVE and PVE are pretty interchangeable,” added DenUyl, who says both programs are funded by Homeland Security, rely on discredited studies about how to predict who might become a terrorist, and face heavy opposition within the communities they purport to help.

“It’s still being funded by the Department of Homeland Security, and that was something that wasn’t made widely known,” DenUyl noted.

The federal funding role was news to Ishaq Pathan, deputy director of the San Jose-based Islamic Networks Group, one of a dozen nonprofits that failed to get the PVE grant.

The group came into existence in 1993 to help educators teach the basics of Islam under statewide religious curriculum guidelines enacted four years earlier, Pathan said.

Pathan, who submitted his group’s grant application, says ING essentially wanted to do more of what it was already doing. The project’s primary goal was to send interfaith speaker panels—made up of Christian, Jewish, Muslim, Hindu and Buddhist religious leaders—into classrooms and community settings to share how extremism comes in all forms and discuss the engagement and education needed to prevent it.

“Currently there’s such a focus on Muslims and extremism,” Pathan reasoned. The speakers bureau, he said, was a way of “intentionally engaging other groups to counter our stigma.”

The grant would have also supported ING’s effort to put the panels in front of government officials and “other influential leaders” who might most benefit from hearing that message, Pathan said. “That program did not get funded.”

That may be a blessing in disguise, Pathan acknowledges. He and his executive director are sensitive to the controversy surrounding the CVE program and share their community’s distaste for the money it offered charities in exchange for “spying on Muslim communities,” Pathan said. “We would not want to be involved with CVE.”

But Pathan says he researched the PVE grant, compared it to the CVE model and found it more inclusive in its language and purpose.

“The huge thing about CVE is it just targets Muslim groups,” Pathan said. “The state of California, we trust them hopefully to not stigmatize communities.”

According to public records obtained by SN&R, 17 nonprofits around the state applied for a portion of the $624,824 California received from Homeland Security. CalOES, which structured the grant, chose five community nonprofits to receive as much as $125,000 apiece over 18 months.

Pathan’s group wasn’t one of them, but two of the five recipients work with primarily Muslim populations.

Pathan and ING executive director Maha Elgenaidi don’t know why their proposal wasn’t selected. In an email obtained by SN&R, Elgenaidi asked CalOES “why we scored so low” on the grant application. In an email to SN&R, Elgenaidi said she never learned the answer to her question. Pathan could only speculate why ING wasn’t selected.

“It may be because that ultimately wasn’t what they were looking for,” he said of his organization’s pluralistic approach to preventing religious extremism. “We’re sad we weren’t able to do this project, but maybe it’s for the best.”

Alam called the grant award to Human Assistance & Development International, or HADI, “the most concerning one for me.” The primarily Arabic language program plans to use its grant to train 20 teachers in the San Bernardino City Unified School District to “understand and recognize extremist ideologies in their community, identify youth risk factors and behaviors that may be associated with violent extremism, elevate civic conversation and positive alternative narratives to extremist thought in their classrooms, and engage appropriate supports and services for youth at risk of radicalization to violence,” CalOES stated in a release.

Students at San Bernardino City schools are 95 percent nonwhite and 88 percent socioeconomically disadvantaged, according to state education data. A quarter of students are English learners.

“The question is what exactly is the premise here—that low-income communities of color are more prone to radicalization?” Alam said. “You really have to ask yourself what’s going on.”

The CEO of the HADI program didn’t respond to an email requesting an interview. A CalOES spokesperson didn’t respond to SN&R before deadline.

Whether intentional or not, President Donald Trump’s broadsides on immigration may make nonprofits more willing to apply for ill-fitting government grants.

Debra DeBondt said it’s called “’mission creep,’ when you become so desperate to get funding you start moving outside of your mission.” DeBondt is the interim CEO at Opening Doors, an organization she first joined in 2001 when it was much smaller and existed under a different name.

DeBondt believes Opening Doors has built a financing infrastructure over the years to avoid chasing after flavor-of-the-administration grants, but the president’s sharp reduction in refugee arrivals means less money for the nonprofits that serve this population, four of which are in Sacramento County. According to a report from the Congressional Research Service, there was a 57 percent drop in the number of Special Immigrant Visas issued to Iraqis and Afghans who worked for the U.S. government or acted as interpreters under the first two years of the Trump administration, from 18,612 in 2017 to 8,023 last year. Opening Doors has laid off staff as a result.

“I won’t speculate as to whether it’s purposeful or not, but the effect is destabilizing on the infrastructure that took years to build,” DeBondt said. “That did a number on all our budgets.”

According to the tax-exempt filings available from Foundation Center, Opening Doors had its best years under President Obama. In 2016, it reported more than $2.9 million in total revenue. Nearly $2.3 million of that came in government grants alone. The Trump administration has been far less kind than the one before it, both to refugees and the organizations that aid them.

“We’re reeling, but we’re not closing our doors,” DeBondt said.

Be the first to comment on "Does program help American Muslims—or spy on them?"