Hollywood 1969…you shoulda been there!”

By Omid Manavirad

Editor’s note: This review contains spoilers

In “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” released July 2019, Quentin Tarantino giftwraps his ninth feature film as an alternate history of 1969 Hollywood that culminates with the events that took place on 10050 Cielo Drive in the night of August 9, 1969. In Tarantino’s tale, the Manson family didn’t murder Sharon Tate.

Instead, they meet a brutal end at the hands of a flamethrower-wielding Leonardo DiCaprio, portraying fictional TV cowboy Rick Dalton, his loyal stuntman, Cliff Booth, played by Brad Pitt and one loyal pitbull named Brandy.

Production for an upcoming spinoff film from the director of “Se7en” and “Fight Club” already began in July 2025. “The Adventures of Cliff Booth” is being helmed by David Fincher and sees Brad Pitt reprising his role as Cliff from “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood.”

In preparation for the spinoff, Movie Notes is diving into the real-life events behind this film and the central element of the entire story.

This film is about the city of Los Angeles as much as it is about the short-lived fame of aging spaghetti western actor Rick. Tarantino captures the City of Angels as the 1950s’ “Golden Age of Hollywood” – that saw names like Alfred Hitchcock and Marilyn Monroe emerge – fade into the dawn of what would become the 1960s-80s’ “New Hollywood.”

“Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” follows Rick, once the star of the series “Bounty Law,” as he watches his career fade amid Hollywood’s shift toward a new generation of filmmakers and young stars.

Between reciting lines in his pool and making margaritas, Rick and his trusty stuntman, Cliff, are the center of a story that orbits the life of Sharon and her husband Roman Polanski, who in 1969 lived with Tate in their home on Cielo Drive.

As Rick’s personal assistant, it’s implied that Cliff does the major stunt work for Rick. But as a World War II veteran who returned home and ended up killing his wife, Cliff is left out of work.

While Rick plays a tough onscreen persona, off screen he affirms a particular stereotype of classic ‘60s actors who may have projected vanity or insecurity but maintained loyal friendships and a strong work ethic.

Cliff is the foil to Rick – a secure, self-reliant war veteran and handyman – allowing their friendship to provide a stark contrast that rests at the center of the film.

While fixing Rick’s TV antenna on the roof, Cliff’s mind wanders to the day when he handily kicked Bruce Lee’s butt during a break on the set of a film shoot, thus being fired. Shrugging his shoulders, Cliff goes back to fixing Rick’s TV antenna.

In a simple, ambient sequence, Sharon (Margot Robbie) runs errands in Westwood, coasting down Wilshire Boulevard in her 1969 Porsche 911L and buying a movie ticket to see herself in “The Wrecking Crew.” The audience is taken back in time to a quieter era.

Instead of the layered exposition from Vincent and Jules in “Pulp Fiction,” or the katana-wielding vengeance in “Kill Bill,” Tarantino leaves room to breathe. No dialogue; just film grain and the 1969 sound foley function as a tribute to Tate.

The real-life Manson, having been experimented on by the CIA, adopted a messiah-like persona in which he used to brainwash and subjugate a group of twenty-year-olds. Prophesying an end-times apocalyptic war where mankind would rise again, Manson proclaimed he would rise to power in that dystopian apocalypse and return to preach his twisted gospel.

Tate, Jay Sebring and the other three young Hollywood insiders were murdered on Cielo Drive on August 9, 1969.

When speaking of Tate’s life history, Tarantino said he thought it was “horrible” that the actress has been “defined by her murder.” It’s no wonder Tarantino exacts his revenge on Manson’s hypnotised hippies in brutal, ruthless fashion.

In “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood,” the Manson family was stopped from their heinous crime. Tarantino poetically punishes them for denying Hollywood and cinema itself, the next eternal, luminous and untouchable goddess-fated vixen. He doesn’t just rewrite history; he rewrites fate as a fairytale.

In 1969, Tate was not yet a starlet in the cloth of Marilyn Monroe, but more free and unbound by the rigid female archetypes from the 1950s “Golden Age of Hollywood.” Her role as Freya Carlson in “The Wrecking Crew” serves as an example, with a scene of Tate – who at the time trained with Bruce Lee – kicks, chops and flips her way through a full fight scene.

For the ‘60s, this was a new aspect of femininity on the silver screen. Tate embodied not just glowing beauty and platinum blonde curls, but a California glow that kicked butt and looked good doing it.

Tate, in real life and in Tarantino’s fairy tale, is a young life preserved, barefoot and carefree.

Elevating the tragedy of her murder, Tarantino saves her, literally casting her assailants into Hell via Rick’s cleansing flamethrower with a face full of glass and a couple of bullets.

This film’s cast is absolutely stacked with talent in every inch of the frame. Members of Tarantino’s Manson family include Austin Butler, Mikey Madison, Maya Hawke, Margaret Qualley and Sydney Sweeney. Timothy Olyphant, Dakota Fanning and Al Pacino also make notable appearances.

Before starring in the 2022 “Scream” reboot, Mikey Madison stood out for her portrayal of Manson Family member Susan ‘Sadie’ Atkins. As the knife-wielding wacko who takes a can of dog food to the face and eventually meets her demise via Rick’s flamethrower, her portrayal reflects the effect Manson’s influence had on them.

Sadie is portrayed as untethered, manic and unhinged; ready to punish others to show her utter devotion to Manson. Her character’s deplorable nature is a testament to Madison’s acting.

So on the night of Aug. 9, 1969, Rick returns to America after making a modestly successful run of Western films in Italy. He and Cliff share one last night of drinks together before parting ways professionally.

That same night, the Manson Family arrives on Cielo Drive with plans to murder Sharon and her friends. Instead, they choose Rick’s house after he angrily confronts them on the street, chastising them for being hippies.

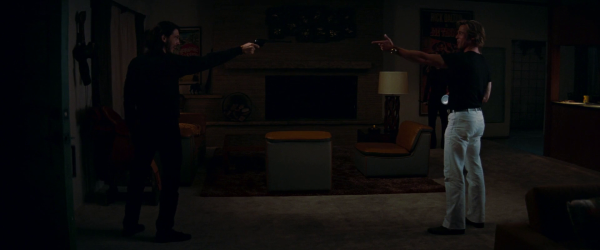

This change of course rewrites history. Inside Rick’s home, Cliff fights the intruders with the help of his pitbull, Brandy. The attack ends in spectacular fashion when Rick finishes the last attacker with the same flamethrower he once used on a movie set.

During the final act, Tarantino breaks down the night of August 9 by the hour; its pacing slows down to a night on the town, and it is superb. Every scene feels substantial as he sets up the climax of events that serve the film’s inception.

Not only is it an enjoyable viewing experience, but it is Tarantino at his most self-aware.

From executive meetings over drinks to scenes of Rick crashing out in his trailer, nothing about this movie feels excessive. In fact, with Tarantino’s filmmaking method, more is better. The film closes with Sharon inviting Rick up to her house, a symbolic moment suggesting that in this version of Hollywood, both history and Rick’s fading career get a second chance.

The film is an exploration of Hollywood’s history and controversies, much like the sprawling landscape of Los Angeles. The elusivity of fame and the fragility of life and dreams are central to the stories of Rick, Cliff and Sharon.

As an auteur, Tarantino’s product is vivid, intense, picturesque and breathtaking. His cut-ins typically focus on tobacco, drinks, food, celluloid film… and feet? The film breathes, smoothly moving along like a grainy documentary that is part dream and part reality.

To the end, “Once Upon a Time in Hollywood” is a love letter to cinema, Hollywood and the history of filmmaking. This movie is certainly worth experiencing, as it is an entertaining and engaging film for the entirety of its duration.

Be the first to comment on "Movie notes: Looking back, ‘Once Upon a Time in Hollywood’ was Tarantino’s fairytale love letter to cinema"