By Scott Thomas Anderson

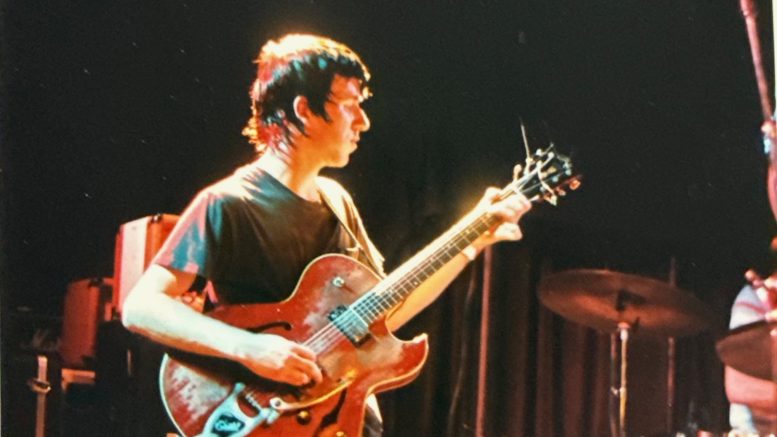

Greg Brown walked onto the stage of the Crest Theatre, picking up his Guild Starfire guitar and scanning an ocean of young faces that filled its auditorium.

It was a summer night in 1995.

I was watching near the front, one of countless aspiring musicians there to see the Sacramento band who’d actually managed to get their song “Jolene” significant radio play. Cake’s singer, John McCrea, began cracking the cadence-like rhythm of “Ruby Sees All” on his acoustic.

And then Brown started to play.

He was conjuring this magically modest outlaw snarl unlike anything we’d heard before.

As the band locked in, Brown’s notes were everywhere, driving their proto-garage bite forward with ringing hints of the Bakersfield Sound. Later, as Cake was amping the audience up with “Jolene,” Brown dominated its climax, his Guild’s savage squawk masterfully evolving into an explosion of 1970s pedal-bent sickness.

Anyone who fiddled with six-strings probably understood that Brown was doing something most musicians only dream of — creating a captivating sound that was entirely his own.

Brown also played like a man possessed, though he had a Zen-type calmness while doing it.

“It’s hard to put a finger on what made him so unique as a guitarist, but he definitely was,” recalled Joe Johnston, the sound engineer who recorded “Jolene,” “Ruby Sees All” and a slew of Cake’s early songs at his studio Pus Cavern. “He was jazzy and played country with a rock attitude. Cake, as a whole, had an approach unlike any band I worked with before or since. And if you heard a Greg Brown guitar part, it was one of those things where you pretty much knew it was him playing.”

But what no one could have guessed on that June night at The Crest was that Brown and his bandmates were on the cusp of launching a particular song across the world, one that, to this day, is arguably the most famous musical composition to ever come out of Sacramento.

Brown’s writing and guitar work on “The Distance” made it an intense but strangely introspective rock anthem.

The track appeared on Cake’s second album, “Fashion Nugget,” which marked Brown’s last studio outing with the group.

On Saturday afternoon, Cake announced on social media the Brown had passed away after a brief illness.

“His creative contributions were immense,” its members said in a statement, “and his presence – both musical and personal – will be deeply missed. Godspeed, Greg.”

While “The Distance” was a smash hit, Sacramento music-lovers also know that Brown’s legacy is broader and multi-faceted.

“He always liked to transform real life into musical paintings,” reflected Keara Fallon, an art director who worked with both Cake and Brown’s second band, Deathray. “His songs were so vivid. Their storylines were abstracted, but you could visualize what he was writing about.”

Fallon knew Brown for 35 years and remained friends with him to the end.

“He was a man of few words,” she said. “He liked to speak about his life through his music, more than he would ever say out loud.”

Brown co-founded Deathray in 1998, along with former Cake bassist Victor Damiani, drummer Michael Urbano and the popular lyricist and singer Dana Gumbiner. In 2000, then-SN&R music reporter Jackson Griffith wrote that Deathray’s tunes moved with “the acutely sharp melodic propulsion found on old Beatles, Kinks and Zombies records, framed by the kind of neurotic edginess perfected by the Cars in the late ’70s.”

Similar to Cake, Deathray was soon signed to an imprint of a national record label. Their self-titled debut album was produced by Eric Valentine, who also helped put out some of Smash Mouth’s biggest hits. Drummer James Neil and keyboardist Max Hart joined Deathray as the band started touring nationally.

“I had the best time touring with them in this late-model Ford Econoline van,” Hart remembered. “It was so much fun, and Greg was incredibly gracious to me. Looking back now, I think I was a little bit of a ham when it came to my stage presence at that time, but Greg was even supportive of that. He was open to all kinds of music, and a musician’s musician – basically a guitar savant.”

Deathray made two more albums and remained a top draw at Northern California venues for years.

“There’s no way to articulate how much Greg’s friendship and creative partnership meant to me,” Gumbiner wrote as part of lengthy public meditation on his friend’s passing. “He quietly and comprehensively changed my life and the lives of so many in his orbit … Anyone else in the world could patch in an old Guild through a ProCo Rat into a Silvertone twin twelve, but no one had his voice. I’m so proud and privileged to be witness to that voice.”

Friends say that, after Deathray, Brown settled into family life and took a public works job in Sacramento. He had a reputation as a genuinely devoted father. Brown recently retired, partly so he could begin playing music again. In addition to performing at Fallon’s 50th birthday party, Brown took the stage at Sacramento’s Side Door in 2024, where he was on a joint bill with Gumbiner and performed alongside Urbano.

“He had a massive amount of conviction,” Urbano shared on Instagram over the weekend. “He could get me behind him without saying a word. I paid attention and was inspired by him endlessly.”

Fallon stressed that, in addition to working with Urbano on projects, Brown was also keeping in touch with all of the musicians who’d originally helped build his career.

“Everyone in Sacramento loved him,” she observed. “He was just one of those gentle hearts.”

gregs father went to sac state with me–greg came to my house and always played my mandolin and guitar when he was a teenager–his wedding reception was at the senator hotel–he went to sac high and was in the creative arts program-he was my son victors best friend-rest in peace greg–look up death ray-greg brown and listen to 20 songs with dana gumbiners amazing voice and todd ropers drums—–tony damiani–his best song stop- drop AND ROLL was never released-victor was gregs sons godfather