Historian, Sierra College professor Gary Noy delves into a sublime, sometimes painful past in ‘Nature’s Mountain Mansion’

By Casey Rafter

Yosemite’s stunning landscape has been a muse to poets, painters and scholars – its peaks and valleys offering an array of colossal sights and shifting forest light. These 1,200-square miles of guarded majesty have always quietly called to creatives, who in turn have fixed their wonder on the heights of Half Dome, the sequoias of Mariposa Grove or the sheer cliffs of El Capitan.

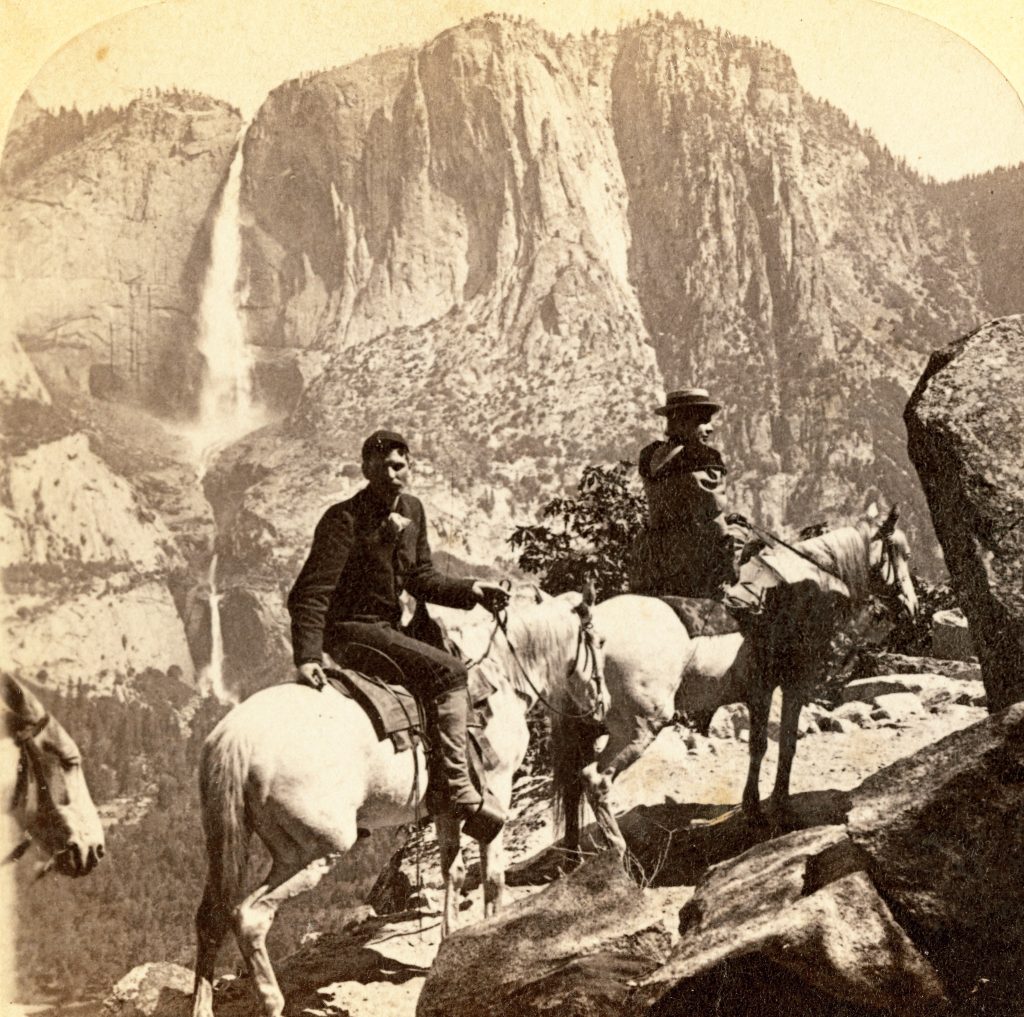

Covering from the time explorers first made their way through the Yosemite Valley in the mid-1850s, historian Gary Noy’s latest book is an ambitious anthology of California’s most-loved national park.

Though Yosemite was already settled by several Native American tribes by the time white settlers commandeered it, the new interlopers did plenty to document their dramas, sagas, and even their crimes, there, over the long century that followed. That much is clear in Noy’s latest offering from Bison Books, “Nature’s Mountain Mansion: Wonder, Wrangles, Bloodshed, and Bellyaching from Nineteenth-Century Yosemite.” In its pages, Noy provides fiction and non-fiction entries, from fables to government records — all painting a vivid picture of Yosemite’s history in a bygone era.

Noy’s earliest memory of Yosemite calls back to being 10-years-old, traveling with his father, a former gold miner. Noy said that, after his dad retired from mining, he became a teacher and enjoyed taking his family on trips all over the Sierra foothills in search of old prospecting camps. One such trip found the Noys standing under the shadow of Half Dome — a spot that the grown author and historian often makes a point of returning to.

“There was a meadow right at the base of Half Dome and there was a grouping of deer there,” Noy remembers with a hint joy. “I was kind of a suburban kid and I hadn’t really seen many deer and to see the deer in that setting — this extraordinary cathedral of granite was just so memorable.”

In the preface of “Nature’s Mountain Mansion,” Noy introduces Sue A. Sanders, a leader of the Illinois chapter of the Women’s Relief Corp, who traveled the western states as a delegate to the Grand Army of the Republic in 1886. During Sanders’ journey, she visited San Jose, Albuquerque, Denver and eventually made her way through Yosemite: She kept travel diaries that Noy drew from to illustrate Yosemite’s glory in the earliest pages of his book.

“Sanders is almost rendered speechless,” Noy writes, describing the traveler’s arrival at Yosemite.

From Sanders’ excerpt: “For a moment, all is silence.” She goes on to describe many oohs and aahs she and nearby visitors experienced over the wonder and amazement before them.

Noy says Sanders’ experience mirrors that of nearly every visitor to Yosemite then and since.

“All the rest of her story, she was just incredibly effusive about everything and incredibly detailed,” the writer reflects. “I thought the contrast between her incredible detail, and the fact that she was just dumbstruck, was just so impressive that I wanted to start with that. I thought it was a very compelling excerpt.”

Gary Kurutz is the former principal librarian of the Special Collections and California History sections of the California State Library. He’s known and collaborated with Noy for years, eventually writing the forward for Noy’s book “Gold Rush Stories.” Noy calls Kurutz a “titan of California historical scholarship.”

“And he’s a friend of mine and a colleague,” Noy acknowledges. “I always turn to him for advice.”

Kurutz had similarly complimentary things to say of Noy, stressing that the historian’s books read much more fluidly than most titles connected to academia.

“Gary was always such a wonderful interpreter of California history,” Kurutz notes. “He was able to really communicate that enthusiasm for California, the great natural history of California.”

Inspiration to edit this anthology came to Noy in the wake of a substantial back injury. His friends and frequent collaborators Joe and Lynn Medeiros gave him an opportunity to recover in their home. As Noy remembers it, the muse to begin the book followed shortly.

“While I was sitting there, I couldn’t do anything,” Noy admits. “I cranked up my brain cells and started thinking about what became this Yosemite anthology.”

Kurutz believes Noy’s choice to collect the many first-hand eyewitness accounts of early visitors to Yosemite amounts to a quite relatable read for many – including him. Kurutz first went to the park in 1975 with a group from the California Historical Society.

“To look up at El Capitan — to me, that was such an awesome sight to see and Yosemite Falls,” says Kurutz. “There are inspiring things, nature’s grandeur as they say.”

Noy’s book illustrates the bounty of California’s treasure, but also reminds us that the land tread upon by awestruck park visitors was once occupied by Native tribes. Ultimately, seven of those tribes saw their numbers dwindle to near extinction in and around Yosemite. Today, the remnants of these indigenous groups remain in the Southern Sierra Miwuk Nation, Bishop Paiutes, Bridgeport Indian Colony, Mono Lake Kootzaduka’a, North Fork Rancheria of Mono Indians of California, Picayune Rancheria of the Chukchansi Indians and the Tuolumne Band of Me-Wuk Indians.

“There is a group — a council that reflects the diversity of the native people that ultimately inhabited Yosemite,” Noy says of the region’s remaining native peoples. “It’s representative of a rather large geographical region because there’s so many tribal clans and groups that are part of this mix of Yosemite’s culture.”

After sorting through volumes of Native American mythology, Noy can’t decide on which story is his favorite, but he admits being rather taken by the legendary origin of what is now known as Ribbon Falls. According to Noy, the falls were known by natives as Virgin’s Tears.

“It was the story of a young woman who lost her lover, essentially before their marriage,” Noy explains. “She was weeping, and it led to this waterfall. I always thought it was…very evocative and I still prefer that Virgin’s Tears name for the waterfall.”

The treatment of native inhabitants by any US entity is shown to be vicious in Noy’s anthology, to the surprise of no one. The historian indicates that an apprenticeship provision was put in place in 1860 to allow white persons to petition for custody of native children. This allowed the displacement of some 10,000 “Indian children” who were sold into servitude before President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation.

“Horrors: I think there’s no other term that can be used other than that,” Noy stresses. “There was an Indian School — a boarding school — and there are reports of massive abuse and cultural destruction. It’s similar throughout the entire system that was established in the late 19th century.”

“The National Parks deliberately wanted to remove the native population because it was distracting to the visitors,” Noy continues. “It was certainly true for the native population in Yosemite. They were not only physically removed from the valley, they also were put into these abusive schools.”

The focus of “Nature’s Mountain Mansion” is narrowed to 19th century Yosemite, but Noy thinks a lot of the themes, conflicts and atrocities brought forth in it are still relevant discussion topics today. As an example, he mentioned the conversations defining conservation or preservation versus commercial development.

“We’re going through racial reckoning and one of the things that happened in the 19th century in Yosemite is the treatment of the native population,” he says. “Toward the end of the 19th century, there started to be at least some discussion about rectifying the tragedy that happened to the native population. What is the appropriate level of commercial development in the national park or state park? That has been an ongoing debate.”

Be the first to comment on "Sacramento author captures the splendor and brutality of Yosemite in the 19th century"